- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog

Blog

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

-

Art

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Blog

- Shop

Out from storage: French portraits

by Peter Jonathan Bell, Associate Curator of European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

7/13/2018

French Portraits , European Paintings , Curatorial Blog

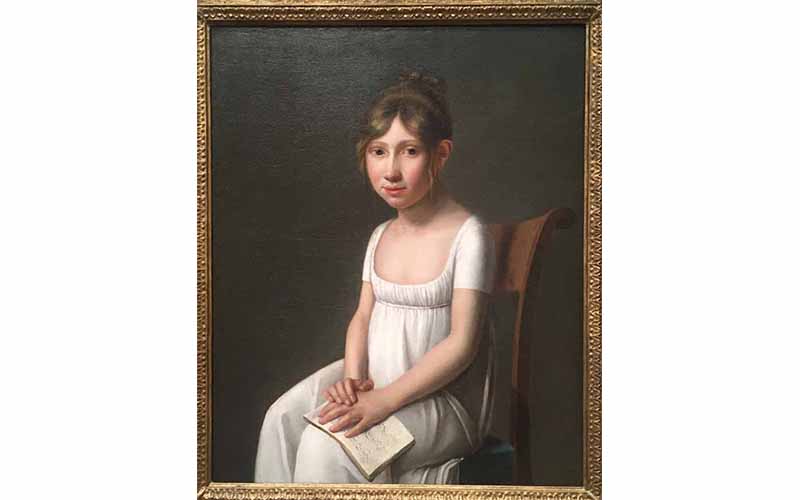

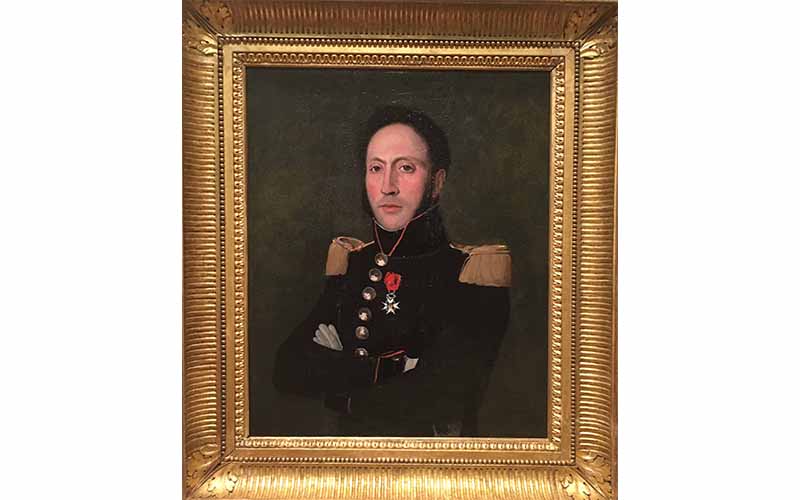

About a month ago the Cincinnati Art Museum welcomed two new faces into our nineteenth-century European galleries – a girl with a song book in her lap and young man in uniform.

We don’t know who the girl is, but in recent years the identity of the artist who portrayed her has been reclaimed. Sophie Guillemard is one of hundreds of female artists working in late-18th and 19th-century France whose identities have been overshadowed by more famous male contemporaries such as Jacques-Louis David. Guillemard was a noted artist in her day exhibiting seventeen times in the Salon, the distinguished annual exhibition of contemporary art in Paris. This sensitive portrait was one of her entries in 1801, the first year she participated.

To the right of our musical girl, and made almost thirty years later, is a portrait by Camille Corot, a much more famous artist, but one best-known for his landscapes. In fact he painted portraits only for his friends and family, and did not display them publicly. Our officer is Auguste Faulte du Puyparlier, one of the artist’s closest friends, and the first owner of the painting. The portrait was later in the possession of other mutual friends of the artist and the officer. It has sustain some damage and loss to areas of the paint layer during the century and a quarter before it came to the Museum, but has benefited greatly from the recent attention of our paintings conservator, whose treatment restored the overall legibility of the painting and the relationship between the sitter and the background. The portrait now communicates much of what the artist intended with the stark setting and his economical rendering of his friend’s face and jacket—a composition and painting style as direct as the sitter’s placid, assured address to the viewer. The frame, too, has had been cleaned to reveal the brilliance of its original gilding.

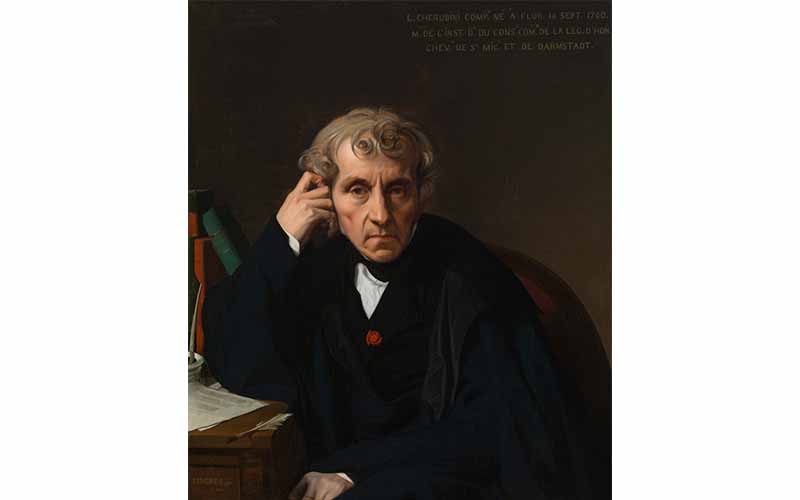

These two paintings now hang across the corner from the brooding portrait of composer Luigi Cherubini by Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres. Together the three pictures take us through a variety of portraiture from the first half of the nineteenth-century. From Guillemard’s unexpectedly frank portrayal of a girl interrupted in the midst of a domestic routine, through Corot’s posed but highly personal friendship portrait, to Ingres’s more official portrait of Cherubini, which is emblazoned at the upper right with a list the composer’s honors.

Each figure looks directly out of the picture at us. Although characterized differently, each seems to express a confidence in the face of our examination, returning our gaze. When we are standing among these paintings, the great skill of their creators is demonstrated by the bodily presence the images impress upon us. As important as this physicality is the sense of physiological depth the artists are able to achieve, allowing each sitter’s identity, even aspects of their personality, to come through clearly to us, the viewers, as we regard them in the museum gallery at a distance of four thousand miles and a century and a half or two from the artists’ studios.

As we look forward to reinstalling the suite of 19th and 20th century European galleries, testing new groupings on the gallery walls, and bringing art works out of storage offer valuable insight to what ‘works’ and what doesn’t. This corner of gallery 225 presents compelling works of art from an important genre of painting in dialogue with one another—and with us, the viewers—that provide access to a fascinating moment in history and art, and another world of beauty and humanity. I hope you can visit them soon!

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

The Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the generosity of tens of thousands of contributors to the ArtsWave Community Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: