Celebrating Hispanic and Latinx Heritage

by Cincinnati Art Museum

9/14/2022

In honor of National Hispanic and Latinx Heritage Month (September 15–October 15), the Cincinnati Art Museum joins institutions across the country in paying tribute to the generations of Hispanic and Latinx peoples who have influenced and enriched our nation and society.

Enjoy these works by or about Hispanic and Latinx artists in the museum’s permanent collection.

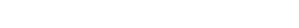

Emilio Amero (1901–1976)

Emilio Amero (Mexican, 1901–1976), The Gesture, color lithograph, Museum Purchase, 1950.12. View online.

Emilio Amero was born in Ixtlahuaca in northwest Mexico. His family moved to Mexico City, where he studied art. He was hired in the 1920s to draw pre-Hispanic artifacts at the Department of Ethnographic Drawing run by Rufino Tamayo (1899–1991). In 1923, he assisted José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949) on the murals at the Escuela National Preparatory School. He traveled to New York, where he worked with the master lithographer, George C. Miller (1894–1965). Upon returning to Mexico in 1930, he opened a lithography workshop at the Escuela de Bellas Artes (National Fine Arts School). The United States became his permanent home in 1933, where he taught and produced several murals. In 1950, The Gesture, with its bold forms and brilliant color was selected for the museum’s First International Biennial of Color Lithography from which it was acquired.

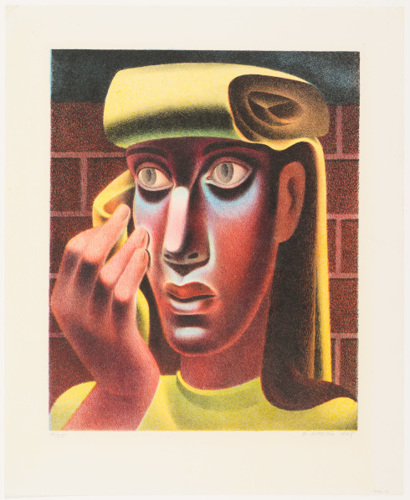

David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974)

David Alfaro Siqueiros (Mexican, 1896–1974), Nuestra Imagen (Our Image), 1947, lithograph, Gift of Elaine and Arnold Dunkelman, 1982.26. View online.

A devoted social activist, David Alfaro Siqueiros was familiar with oppression and subjugation. He had fought against facism in the Mexican Revolution (1910–20) and the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). A committed social activist, Siqueiros used his voice as a labor union advocate and member of the Mexican Communist Party. For this lithograph, Siqueiros used a photograph of a young male model taken by his collaborator in Mexico, Leo Matiz (1917–1998). It was printed at the collaborative workshop Taller de Gráfica Popular. The organization believed that to serve the people, art must reflect the social reality of the times. A nonmember, Siqueiros created his print as a workshop guest. He blends the monumental forms of Aztec and Olmec sculpture with the portrayal of proletarian struggle against racism, imperialism, and capitalist exploitation. His painting of the subject resides at the Museo de Arta Moderno in Mexico City.

José Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

José Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Spanish, 1746–1828), Disparate Alegre (Merry Folly), circa. 1816–17, etching, burnished aquatint, and drypoint, Bequest of Herbert Greer French, 1943.526. View online.

José Francisco de Goya y Lucientes was born in 1746 in Fuendetodos in the province of Saragossa. He died in Bordeaux at the age of eighty-two, in exile from his native country. Against the backdrop of the Enlightenment and the Napoleonic wars, Goya’s unique genius established him as the foremost Spanish painter and one of the world’s great printmakers.

Goya created four major print series, but only two were publicly issued during his lifetime: Los Caprichos in 1799 and Los Tauromaquia in 1816. His later series, Los Desastres de la Guerra (1810–14, 1820–23) and Los Disparates (circa 1816–17), were never published during his lifetime because of the fluctuating political climate.

The Spanish word disparate means “folly” in English. Los Disparates remain shrouded in mystery. Goya distills, transforms, and twists their social, political, and religious significance to the point that it defies explanation. His evocative titles and innovative themes remain the most ambiguous and enigmatic of any of his print series. None of the plates were dated nor can they be pinpointed to external events. In 1823, fearing that his prints would compromise his safety when Ferdinand VIII revoked Spain’s constitution for the second time, Goya hid his plates along with those from Los Desastres de la Guerra in his country home and sought a legitimate excuse to flee Spain in 1824. Goya’s grandson discovered the prints in 1854, but it was not until 1864 that the Academia of San Fernando published an edition of eighteen Los Disparates plates under the title Los Proverbios. The museum’s impression is a proof before the posthumous edition where the rich aquatint tones and delicate drypoint lines have not begun to wear away.

The six dancing figures in Disparate Alegre are no longer the youthful majos and majas gracefully frolicking on the banks of the Manzanares as in Goya’s 1777 tapestry cartoon. They stiffly totter as if sentenced to dance eternally. It has been suggested that Goya satirized the fate of the nobility who offer society neither merit nor service for their honorific and hereditary titles.

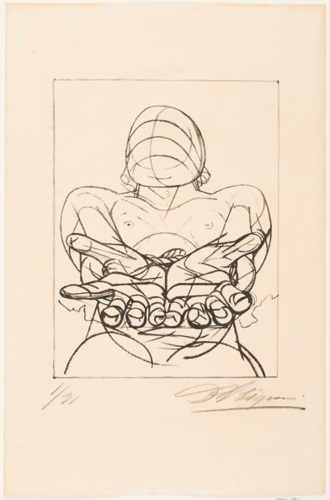

Pablo O’Higgins (1904–1983)

Pablo O’Higgins (Mexican, 1904–1983), Masons, 1942, color lithograph, Museum Purchase, 1948.3. View online.

Pablo O’Higgins was born Paul Higgins in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1904. Dissatisfied with his experience at the School of Fine Arts program in San Diego, California, he became a permanent resident of Mexico City in 1924, changing his first name to “Pablo.” He joined the Communist Party in 1927 and added the “O” to his last name. He became Diego Rivera’s primary assistant on his mural projects at the National School of Agriculture in Chapingo and the Ministry of Education in Mexico City. In 1927, O’Higgins participated in the government’s cultural mission in Durango, teaching national ideologies using art as a didactic tool. In 1937 he joined Leopoldo Méndez as a founding member of the collaborative workshop Taller de Gráfica Popular. The collective provided facilities to edition prints for exhibition and sale and produce graphic art for other organizations, believing art should reflect social reality to serve the people. Masons, depicting laborers, was created at Taller de Gráfica Popular.

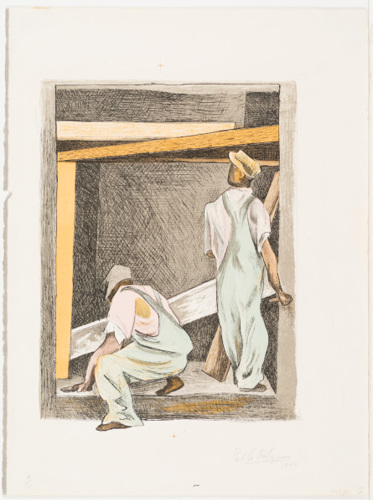

Francisco Dosamantes (1911–1986)

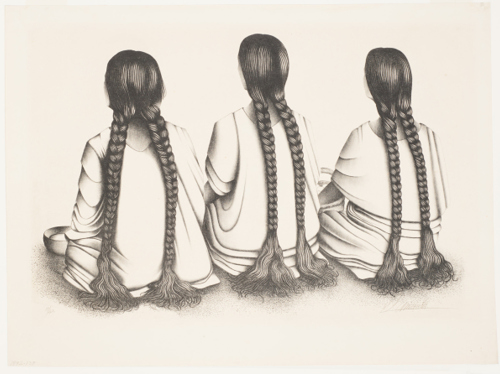

Francisco Dosamantes (Mexican, 1911–1989), Women of Oaxaca (Seated), 1940s, lithograph, Gift of Emily Poole, 1942.139. View online.

Francisco Dosamantes was a participant in the Cultural Missions program as an art instructor. His mission was to educate the rural population on the importance of literacy and their Indigenous heritage through art. He was a full member of the Taller de Gráfica Popular. Dosamantes’s experience in Oaxaca inspired this lithograph. He wrote, “Oaxaca is situated in a semi-tropical valley in Southern Mexico. The women are known for their lovely embroidered huipiles (blouses) and for their long, black, shiny hair worn braided.” The most striking feature of the three seated Indian women with their backs to the viewer is their braids. This type of image, featuring women’s traditional dress, had a great appeal to foreign audiences.

José Ignacio Aguirre (1902–1990)

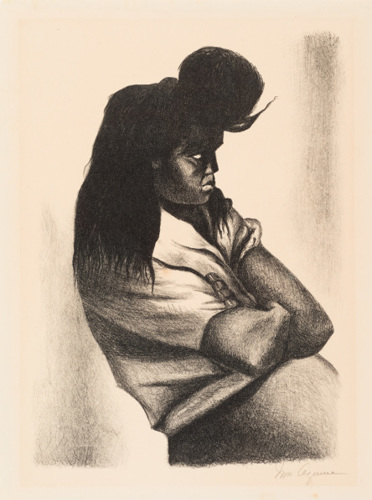

José Ignacio Aguirre (Mexican, 1902–1990), Mexican Girl, 1947, lithograph, Gift of Allen W. Bernard, 2012.57. View online.

José Ignacio Aguirre was born in San Sebastián, Jalisco, a state in Western Mexico, where his family worked in the mining industry. Throughout his youth he gained first-hand experience in life’s hardships as a member of the revolutionary forces. In 1921 Aguirre left Jalisco for Mexico City, where he worked for the government. He was famous for his biting, satirical images as well as portrayals of Mexican women and their hardships. Mexican Girl published by the Associated American Artists, was also published under the title Women in the Coal Line-Up (Mujer en la Cola del Carbon) by the Taller de Gráfica Popular. This dark image underscores the young woman’s rage and frustrations of the turbulent times.

José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949)

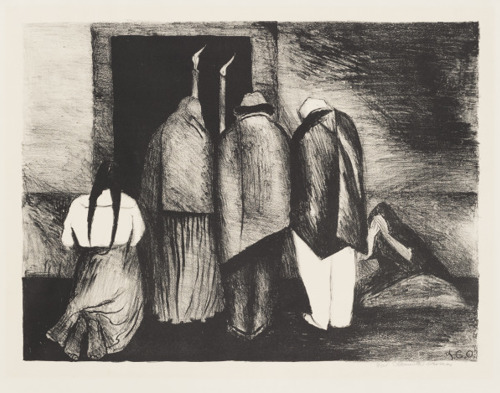

José Clemente Orozco (Mexican, 1883–1949), El Requiem (Requiem), 1928, lithograph, Gift of Herbert Greer French, 1940.410 © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City. View online.

A requiem is a religious observance for a deceased person. In José Clemente Orozco’s lithograph the viewer enters a scene depicting five mourners before a dark doorway. The stillness of hunched figures conveys the heaviness of mourning. The flickering flames provide a sense of movement and contrast with the braids of the kneeling woman. The anonymous figures provide commentary on the human cost of the Mexican Revolution. The American Institute of Graphic Arts selected Requiem for the fourth annual Fifty Prints of the Year publication.

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954)

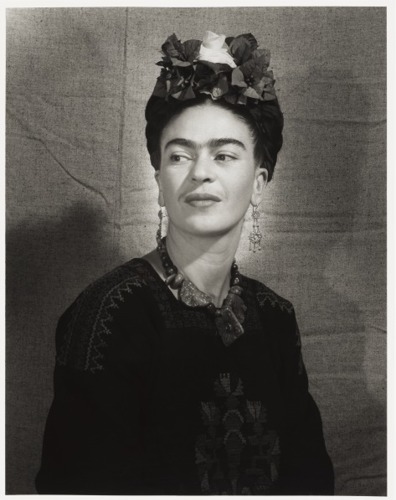

Bernard Silberstein (American, 1905–1999), Frida Kahlo, circa 1940, printed 1984, gelatin silver print, Museum Purchase, 1986.580, © Edward B. Silberstein. View online.

Photographer Bernard Silberstein’s subjects range from travel destinations to commercial products, but among his best-known photographs are his portraits of Frida Kahlo. Taken at her home in Mexico in the early 1940s, these portraits offer insight into how Kahlo presented herself, a practice of self-fashioning that has made her one of the most recognized artists in the world.

Here, Kahlo’s figure is isolated against a plain cloth backdrop. Bougainvillea blossoms and a white rosebud adorn her hair. The corners of her lips hint at the beginning of a smile.

Kahlo collected Indigeous clothing from across Mexico and Central America. She was among the most photographed women of her generation, and she carefully chose her clothing, jewelry, and hairstyle for each photo session, blending elements from different regions to create a visual identity that was distinctly her own. Silberstein’s portrait gives us insight into how she wished to be seen, a glimpse at one version of her public persona.

View more portraits of Kahlo in our online exhibition Frida Kahlo: Photographic Portraits by Bernard Silberstein in partnership with the University of Cincinnati.

Listen to soprano Catalina Cuervo discuss these photographs in relationship to her portrayal of Kahlo for the 2017 Cincinnati Opera production of Frida in this Art Palace podcast.

Joan Miró (1893–1983)

Joan Miró, (Catalan, 1893–1983), Mural for the Terrace Plaza Hotel, 1947, oil on canvas, Gift of Thomas Emery’s Sons, Inc., 1965.514, © 2008 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. On view in Gallery 127.

In 1941, a retrospective of paintings by the Spanish Surrealist Joan Miró, held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, sparked widespread enthusiasm for his work in the United States. This mural, painted in 1947, fulfilled the artist’s ambition to produce a piece of public art, and proved decisively that he could adapt his intimate vocabulary of organic forms and delicate linear arabesques to a monumental painting more than thirty feet long.

Following the recommendation of the Cincinnati Art Museum’s Director Philip Adams, Jack Emery (scion of Cincinnati’s Emery dynasty) commissioned the work from Miró, contracting its creation through the art dealer Pierre Matisse. The mural was originally designed to adorn the Gourmet Room, the restaurant twenty floors up in the Terrace Plaza Hotel, the shining example of the postwar architectural modernism built for Thomas Emery’s Sons, Inc.

Miró came to America for the first time in February 1947 and visited Cincinnati to examine the site. He executed the mural in the New York studio of Carl Hotly, who recalled watching the artist “combine and fuse a craftsman’s method with artistic adventure.” Relating the mural to the blue sky beyond the windows that would surround it, Miró first painted the blue, textured background. He then drew on it in with charcoal, “dusting off” several versions until he achieved the desired composition. Objecting strongly to any literal interpretation of his work, Miró created an individual response to experiences, such as the spectacle of flying kites, that inspired some of the elements in the mural.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Miró’s work in this CAM Look episode published on September 11, 2020.

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

Pablo Picasso, (Spanish, 1881–1973), Still Life with Glass and Lemon, 1910, oil on canvas, Bequest of Mary E. Johnston, 1967.1428, © 2016 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. On view in Gallery 229.

Still Life with Glass and Lemon is an example of Pablo Picasso’s most innovative period of analytic cubism. Developed by Picasso and French painter George Braque between 1907 and 1912, analytic cubism attempted to break down three-dimensional objects into their basic geometric parts, depicting them as if we were viewing them simultaneously from a number of different angles.

As the title indicates, the museum’s painting depicts everyday objects in an almost monochromatic palette: a glass, lemon, table, painter’s palette, rolls of canvas, and curtained windows. However, the composition is so fractured and departs so radically from visual reality that the viewer is left with few reference points. While we can readily identify the curve of a glass, the curdling edge of a roll of canvas, or the uneven contours of the lemon, the painting presents itself as a puzzle that can only be resolved through sustained looking. Eventually, Picasso’s painterly logic emerges: disparate angles and curves give way to unified objects in a single, two-dimensional composition, while the profusion of colored planes forms a rigorous structure.

Listen to a museum docent museum staff member discuss Picasso’s work in this CAM Look/Haiku episode published on July 7, 2021.

Diego Rivera (1886–1957)

Diego Rivera (Mexican, 1886–1957), Miss Mary Joy Johnson, 1939, oil on canvas, Gift of the children and grandchildren of Dr. and Mrs. J. Louis Ransohoff, 1977.210, © 2016 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York. On view in Gallery 228.

Mary Joy Johnson met Diego Rivera when she worked in Mexico as a buyer for American department stores in the late 1930s. When Rivera asked to paint her portrait, Johnson requested that he portray her in the “combined styles of Modigliani and the ancient Chinese masters.” In deferring to Johnson’s wish, Rivera made a significantly departure from his typically robust, solid figures, softening and elongating the sitter’s features, and adopting a calm and soothing palette.

Diego Rivera was one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century. He played a key role in revitalizing the technique of fresco painting in the United States and Mexico. Rivera is best known for depictions of Mexican history and culture, political and social issues, and the development of industry.

Juan Soriano (1920–2006)

Juan Soriano (Mexican, 1920–2006), Bull, 2004, bronze, Museum purchase with funds provided by the family of Robert B. Ott, a trustee of the museum from 1984–1992, in his memory, 2017.60. On view in Gallery 231.

This sculpture’s rugged texture and blocky abstracted form beautifully suggest the power of the bull. The bull’s long and deeply-held associations with Spanish culture appealed strongly to the artist, who turned to the subject on several occasions. This late sculpture relates to an earlier work Soriano produced in ceramic. It is the artist’s proof, made as a prototype for an edition of six bronzes.

A painter, sculptor, and printmaker, Soriano is widely hailed as one of the premier Mexican artists of the twentieth century. He was a modernist who refused to be pigeon-holed to any one style and whose subjects ranged from portraits to mythological themes. Beginning in the 1980s, Soriano created a remarkable group of monumental bronze animal sculptures, many for public spaces. He was the recipient of Mexico’s National Art Prize in 1987.

Listen to a museum docent discuss Soriano’s work in this CAM Look episode published on October 14, 2020.

Rufino Tamayo (1899–1991)

Rufino Tamayo (Mexican, 1899–1991), Dancers over the Sea, 1945, oil on canvas, Gift of Lee A. Ault, 1947.488, Art © Tamayo Heirs/Mexico/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. On view in Gallery 229.

Rufino Tamayo was a Mexican painter and printmaker of Zapotec heritage. Tamayo studied and experimented with European art movements like Cubism, Impressionism, and Fauvism, adapting them through the subjects and styles of his culture.

The elemental forms and mythic figures that populate Tamayo’s compositions stem from the colorful ceremonies and the bold forms of Pre-Coumbian art of his native Oaxaca, blended with influences from European Surrealism. The artist’s sophistication as a draftsman and colorist is evident in the fluid contours, flat areas of color and the complex surface designs of interlocking shapes that distinguish his work.

Listen to a museum docent discuss Tamayo’s work in this CAM Look episode published on June 28, 2021.

Félix González-Torres (1957–1996)

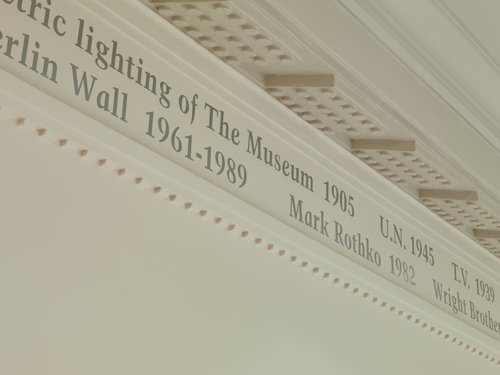

Félix Gonzáles-Torres (American, b. Cuba, 1957–1996), Untitled (Portrait of the Cincinnati Art Museum) (detail), 1994, paint on wall, Museum Purchase: Gift of the Contemporary Collectors Circle, 1994.218. View in the Main Lobby on the first floor.

We usually think of a portrait as a visual likeness of the sitter, specifically reflecting their physical appearance. The subject is often surrounded by telling attributes that reference their character, occupation, and social status. But this portrait is unusual. It tells us about an institution rather than an individual, and the artist has chosen to paint the portrait with words and dates.

Commissioned by the Cincinnati Art Museum in 1994, this work conveys the institution’s character through a text-based string of significant events and their dates. The history of the museum, its affinity to the city of Cincinnati, and its connection to the cultural and political events of the nation can be understood through this listing that encircles the lobby near the ceiling. Purposefully organized in non-chronological order, this seemingly random chain of events also references the sporadic nature of the frailty of memory.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss González-Torres’ work in this CAM Look episode posted on April 23, 2020.

Explore works by Hispanic and Latinx artists in the museum’s open-access photobook collection.

Browse more physically compact, conceptually expansive works of art at your leisure in the Mary R. Schiff Library. Other Hispanic or Latinx artists represented in the museum’s FotoFocus Photobook Collection include Laia Abril, Ricardo Cases, Cristina de Middel, Federico Estol, Guilherme Gerais, Tarrah Krajnak, Alberto Lizaralde, Sebastian Meja, Felipe Russo, Alessandra Sanguinetti, and Mauricio Valenzuela.

Explore more works by or about Latinx and Hispanic artists in the museum’s collection with this self-guided tour through our galleries and while exploring online.