- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog

Blog

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

-

Art

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Blog

- Shop

Notes from Photography Storage: Edward S. Curtis’s The North American Indian

by Eric Hughett, Intern

8/27/2018

Photography , Edward Sheriff Curtis , The North American Indian

The work of American photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868-1952) pervades American culture. Curtis became famous in the early twentieth century for depicting native North Americans, and his photographs helped form the archetypal image of the “Indian” that still features in popular culture today. Nearly everyone has seen a picture Curtis made or that his work has influenced.

The grand project that occupied the better part of Curtis’s life and attention was called The North American Indian. It consists of twenty illustrated text volumes plus twenty portfolios of luxurious photogravures (beautiful photo-mechanically printed photographs), in which Curtis set out to document the native tribes of western North America. The project covers everything from spiritual beliefs to the basics of each tribe’s language. Needless to say, this was a very large undertaking, taking Curtis nearly thirty years to complete!

The monumental nature of the work makes it historically and artistically valuable, so it’s important for the Museum to have a clear grasp of the Curtis material in the permanent collection. One of my jobs as an intern has been to do the necessary research, documentation, and detective work.

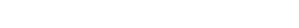

Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952), The Vanishing Race—Navaho (from The North American Indian, Volume 1, Plate 1), 1907, photogravure. Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University.

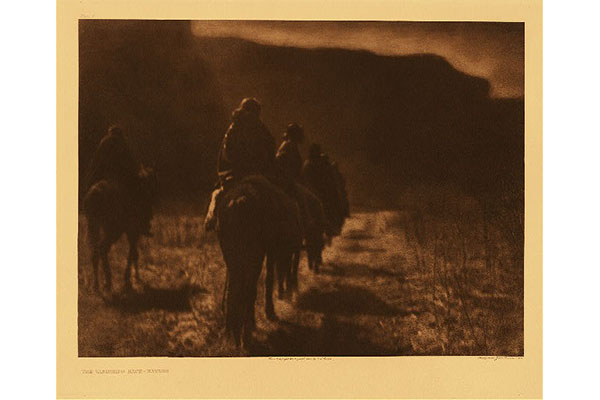

Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952), Red Wing—Apsaroke (from The North American Indian, Volume 4, Plate 120), 1908, photogravure. Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University.

The North American Indian is rare. It was originally published between 1907 and 1930 in a limited edition of 500 – but less than half that number were ever printed. The Museum has the first five volumes and portfolios from edition number 30, which were donated in 1910. Yet the details of provenance, or the history of ownership, are less certain. We know the donor was a wealthy Cincinnati woman named Georgine Thomas, however, we have no record of how or where she got the volumes she gave to the Museum. My research showed that to fund the project, Curtis made the series by subscription—leading me to find a list of the original subscribers, on which I was hoping to find Thomas’s name. I was surprised to discover the subscriber for edition number 30 was one Dan J. Mitchell of Arizona. Unfortunately, we don’t know how they traveled from Mitchell to Thomas, leaving the history of our volumes up to the imagination—at least, between 1907 and 1910.

Once I found out about the people who had owned our Curtis material, it was important to understand the man behind the camera. What could have motivated him to undertake and persevere with such a large project? Artistic pursuit, notoriety, public support from national figures such as Theodore Roosevelt and J.P. Morgan, and the particular moment in American history were all factors. Philosophically, though, Curtis believed that the native peoples of North America were a “vanishing race” that needed to be preserved for posterity. This idea of ethnographic salvation is at the foundation of The North American Indian and informed the ways he chose to depict his subjects.

Finally, the Museum also needs to know practical things about artworks. For example, the photogravures within the portfolios had yet to be measured, and no pictures had been taken of them. I was tasked with recording the dimensions of each individual photogravure and taking reference pictures that help keep track of the works in the Museum’s database. The process was painstaking, but it gave me a chance to work directly with incredible artworks and to become a fast expert on all things Curtis.

Tackling Edward Curtis and The North American Indian was challenging and rewarding. I had to start from scratch, learning as much as possible about the artist and closely examining his works before approaching the tasks of cataloging. I really enjoyed playing detective, digging into documents from the past to piece together the backstory of the artworks in front of me in storage. This project, in the end, gave me insight into many behind-the-scenes aspects of curatorial work, which helped me become more fluent in the mechanisms of the Museum as a whole.

If you’re interested in learning more about The North American Indian, look out for his pictures in the galleries. In the meantime, you can get a digital impression of the complete work through Northwestern University.

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

The Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the generosity of tens of thousands of contributors to the ArtsWave Community Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: