- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog

Blog

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

-

Art

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Blog

- Shop

Beauty & the Eye of the Beholder

by Peter Haffner, PhD, Assistant Professor at Centre College and Drew Morris, PhD, Assistant Professor at Centre College

8/24/2023

Centre College , art history , psychology , research , eye tracking , El Greco , Francisco Zurbarán , Giovan Battista Recco

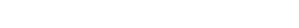

Francisco Zurbarán (Spanish, 1598–1664), Saint Peter Nolasco Recovering the Image of the Virgin of El Puig, 1630, oil on canvas, Gift of Mary Hanna, Mr. and Mrs. Charles P. Taft and Mr. Stevenson Scott in memory of Charles Frederick Fowles, 1917.58

We are Peter Haffner, an art historian at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, and Drew Morris, a cognitive psychologist also at Centre College. This summer, the two of us conducted an interdisciplinary research project bringing together science and art at the Cincinnati Art Museum. Using specialized glasses and software that tracks a wearer’s eye movements, we investigated how people visually engage with works of art. Eyes are a window to the soul, but also the brain. Working with Peter Bell, CAM’s European art curator, we were granted permission to rope off a gallery for two days to see what this technology might reveal.

With the generous support of Jill Cleary, the museum’s visitor services coordinator, we invited 24 staff members, interns, and volunteers across all museum departments to carve out 30 minutes of their busy workdays. When each participant arrived for their time slot, we handed them a tablet on which they filled out a questionnaire and took a survey gauging their knowledge of and familiarity with 41 works of art spanning the last 500 years of Western art history, from Michelangelo to Basquiat. After the survey was completed, we outfitted them with eye-tracking glasses.

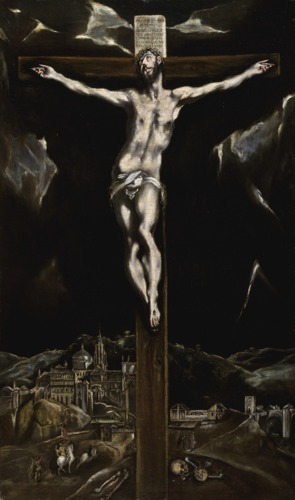

Participants were asked to stand in front of three seventeenth-century paintings in the Dr. Ira and Linda Abrahamson Family Gallery (G206): El Greco’s Christ of the Cross with a View of Toledo; Francisco Zurbarán’s Saint Peter Nolasco Recovering the Image of the Virgin of El Puig; and Giovan Battista Recco’s Still Life with Game.

We chose these three works because of their compositional variety and diverse subject matter. For a duration of two minutes, the glasses tracked the wearer’s eye movements and analyzed their movements for trends.

Much of the data will take time to process and interpret, but some of the immediately available visualizations, so-called “heat maps,” reveal which areas of the canvas drew the most attention. Areas in green show where viewers’ eyes spent some of their time. Yellow and orange denote increasing time, and areas of red indicate where they looked the longest.

Left: El Greco (Greek, b.1541, d.1614), Christ on the Cross with a View of Toledo, circa 1610–circa 1614, oil on canvas, John J. Emery Fund, 1932.5

The heat map of the El Greco painting revealed that participants spent the most time viewing the face of Christ and the text above his head. This lone human face rendered in bright tones, jumps out against the dark background. The view of Toledo in the background also drew a lot of attention, especially the cathedral’s dome. But notice the small, isolated point of red to the left of Christ’s hip. It lies on an area of the canvas that is rendered completely black, an otherwise unremarkable section of the background. Why did viewers dwell on that one spot for so long?

Barring a technological anomaly, one thought, based on our observations, is that the recorded eye movements follow a trajectory beginning at the top of the composition with Christ’s head, down along the S-curve of his torso to the loincloth. Here, a strip of fabric just 45 degrees downward left where the eye is led into the deep darkness of the background, essentially forcing the viewer, through the artist’s compositional choices, to confront a deep, dark void in the painting.

Could this be symbolic of eternity? Is it an ingenious compositional maneuver through which El Greco buttresses the meditative intent of crucifixion paintings? In addition to contemplating Christ’s suffering on the cross, is the viewer compelled to visually confront the vastness of God’s domain and thus motivated to righteous devotion? Maybe that’s overthinking it. That dark area could also just be a “pit stop” for our eyes as they make their way down to the cityscape below. Think of it as the visual equivalent of a rest in musical notation. A place for the viewer to catch their breath, so to speak. Either way, moments like these, quantified in the heat maps, can reinforce our understanding of how artists think about composition as they “build” a picture, and how it serves our overall impression of a work, especially in figurative Western paintings.

We found a second interesting point in the same data. Participants who scored lower on their familiarity with works of art and artists in the survey tended to spend more time looking at the scene of Toledo, while those who scored higher spent much more time looking at the figure on the cross. One might assume that the central figure of Christ on the cross, so dominant in the composition and so boldly rendered, might draw the most attention of any viewer, regardless of their knowledge of or familiarity with major artists and their work. That there was any discernible difference in the viewing patterns related to the participants’ survey scores is fascinating enough, but the fact that the contrast was so stark shows the exciting possibilities of what this type of research could reveal and offers new avenues of future exploration.

As we continue to comb through the extensive data we collected, we hope to share our results with the broader public and offer more opportunities for volunteers to participate in our study, both at CAM and beyond. In the meantime, we want to reiterate our gratitude for the generosity and enthusiasm of everyone we worked with at the museum, especially Peter and Jill, whose cooperation and support were essential to the success of this phase of the project.

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

The Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the generosity of tens of thousands of contributors to the ArtsWave Community Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: