- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Provenance and Cultural Property

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Art Bridges Cohort Program

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Provenance and Cultural Property

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Art Bridges Cohort Program

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

-

Art

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Provenance and Cultural Property

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Art Bridges Cohort Program

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Blog

- Shop

Behind the Scenes in Conservation: A Seemingly Innocuous British Portrait

by Kristopher Reisser, Conservation Intern

6/8/2023

CAMConservation , paintings conservation , cam intern , mather brown , portrait , European Paintings

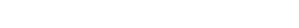

My name is Kristopher Reisser, and I am a third-year art history student at the University of Cincinnati. As the Paintings Conservation Intern for the summer, I’ve had the opportunity to engage with paintings in a way that previously was impossible for me. Over the past few weeks, I’ve been working on a surface cleaning of Portrait of William Frankland (circa 1790) by Mather Brown (1761–1861) an American artist who spent most of his life in England taking commissions from politicians, such as John Adams, and nobles, including the young Prince of Wales (later King George IV). When I read the curatorial file for this painting, I discovered a remarkably expansive biography, not just of the painting itself, but also of the sitter and the artist. What is most interesting to me, though, is the sitter’s story.

William Frankland (1720–1805) was High Sheriff of Sussex at the time Brown painted his portrait and the third son of Henry Frankland, governor of colonial Bengal (today’s Pakistan). The younger Franklin inherited his father’s interest in the Middle East and East Asia, evidenced by the map of the Levant displayed on the table below the sitter’s arm.

But I was most intrigued by the bust depicted in the background of the painting that I believed might be a likeness of Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658), the notoriously divisive figure of English history who ruled Britain after the English Civil Wars. (A childhood viewing of the period-film Cromwell from 1970 spurred my initial interest in the man.) It turns out the curatorial file confirmed my hunch. Historians believe Frankland to be the great-great-grandson of Cromwell through his daughter Frances whose name is written on the medallion in the bottom left-hand corner of the portrait.

With this information, I immediately wondered to what extent public perception of Cromwell had shifted in the 130 years since the Restoration in 1660 and the creation of the Frankland portrait in 1790. Maybe the Cromwell bust had become a neutral image that Brown, perhaps at the request of Frankland, could include as a stoic symbol of his heritage. Would the sitter have leveraged this ancestry for his benefit?

I can happily say that this seemingly innocuous portrait is more interesting than it presents at a first glance, and hopefully I can give William Frankland the spruce-up he needs for the museum’s British paintings catalog project.

Mather Brown (American, 1761-1831), Portrait of William Frankland, circa 1790, oil on canvas, Gift of Alexander F. Anderson, 1945.48

Related Blog Posts

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

The Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the generosity of tens of thousands of contributors to the ArtsWave Community Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: