- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

Understanding the "Heart" of the Bike

by Mackenzie Strong, Curatorial Assistant for Decorative Arts & Design

4/23/2025

What makes a bicycle a bicycle? If I had been asked this question just over a year ago, my answer probably would have referenced the different elements forming the physical structure of this familiar vehicle: geometric frames, two wheels, seats (or saddles), u-shaped handlebars, pedals, and chain mechanisms. Now, after having worked on the museum’s presentation of Cycle Thru! The Art of the Bike, I have a new answer—one that goes beyond the gears and the spokes. Learning about the evolution of bicycle design has also revealed how the bike has become synonymous with ideas of freedom and expression. Essentially, studying the “art of the bike” has provided a new understanding of the “heart” of the bike: its fundamental role not just as a mode of transportation, but as a global vehicle for social change.

Soon after its introduction in the mid-1800s, the bicycle gained popularity as both a utilitarian and an ideological tool. As this new technology and the increased mobility it empowered became available and accessible to more people, many individuals and movements quickly adopted this vehicle as an instrument for their social justice activism. In the 1890s, cyclists of color—like Boston-based Katherine Towle “Kittie” Knox—used the bike to advocate for equal rights and to challenge the increasingly entrenched racism and discrimination they experienced within the cycling community and American society. Early feminists and suffragists similarly used this emerging vehicle in the late 1800s and early 1900s to resist the gendered barriers they encountered. The bike even played an essential role in dress reform at the turn of the century, as designers fashioned novel (and sometimes revolutionary) garments that better accommodated this new form of transportation while simultaneously communicating social and political messages about gender equality.

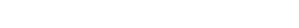

Throughout the 1900s, bicycles continued to act as agents of freedom. British soldiers in the Second World War used bikes—like the BSA Airborne—to oppose fascism in Europe. Modern and contemporary artists also increasingly featured the bicycle in their creative works, harnessing the vehicle’s inherent sense of independence to support their own expressions of identity and autonomy. For example, Japanese artist and activist Mayumi Oda has depicted different bicycle forms alongside her feminist reclaiming of the traditionally male Bodhisattvas within Buddhist teachings. In Manjusuri, the Bodhisattva of perfect wisdom rides a high wheeled bicycle, while the Bodhisattva of shining practice cycles along on a safety bike in Samansabadra.

Today, the bicycle maintains its crucial function as a global vehicle for human rights. The Native Women Ride and Indigenous Cycling Collective movements provide community and resources for Indigenous cyclists while educating about the lands of Turtle Island (North America) and advocating for Indigenous joy. In Palestine, bikes have become central to rallies and demonstrations dedicated to mobility justice. Likewise, Afghan women have cycled through Afghanistan and beyond in resistance to ongoing gender inequities.

Ultimately, over its 150-year history—and throughout every design iteration and innovation—one aspect of the bicycle’s function has remained a constant: its capacity to encourage social justice and change across the globe. So, the next time you spin through the exhibition or cycle along your favorite route, maybe you, too, will reflect on the “heart” of the bike.

Cycle Thru! The Art of the Bike will be on view in Galleries 234 and 235 through August 24, 2025. To learn more about the bicycle’s role in these historical and contemporary social justice movements, watch the recording of “CAM Presents: A Two-Wheeled Revolution” by artist, cyclist, and activist Shannon Galpin, on the museum’s past lectures webpage.

BSA Airborne, 1942–46, Birmingham Small Arms Company (English, 1861–1973), Bicycle Museum of America, New Bremen, Ohio

Mayumi Oda (Japanese, b. 1941), Manjusuri (On the Bicycle), 1980, color screen print, Cincinnati Art Museum; The Howard and Caroline Porter Collection, 1990.812, © Mayumi Oda/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Mayumi Oda (Japanese, b. 1941), Samansabadra (On the Bicycle), 1980, color screen print, Cincinnati Art Museum; The Howard and Caroline Porter Collection, 1990.813, © Mayumi Oda/Licensed by VAGA at Artist Rights Society (ARS), NY

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: