- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Provenance and Cultural Property

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Art Bridges Cohort Program

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Provenance and Cultural Property

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Art Bridges Cohort Program

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

-

Art

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Provenance and Cultural Property

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Art Bridges Cohort Program

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Blog

- Shop

Pride: LGBTQ+ Artists and CAM

by Rachel Ellison

6/18/2019

LGBTQ+ , Pride , staff blog , Zanele Muholi , Georgia O’Keeffe , Andy Warhol

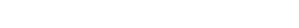

Georgia O'Keeffe, Yousuf Karsh, gelatin silver print, Photograph, Gift of Elaine and Arnold Dunkelman, 1982.215

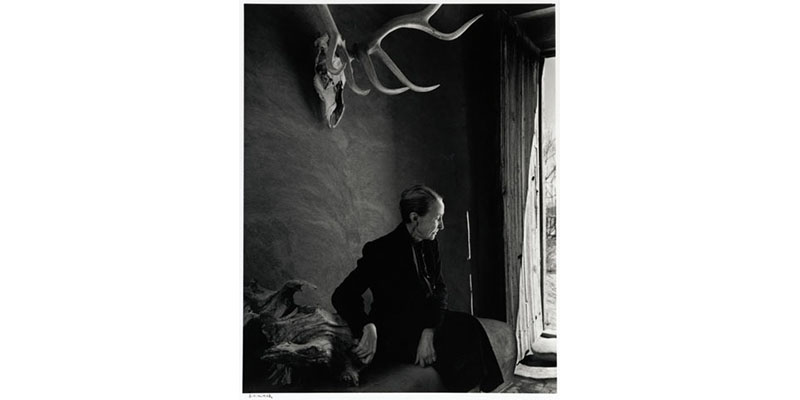

Merce, Andy Warhol, screen print on floral gift wrap paper, Irwin and Judith Hanenson Collection, © 2016 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2009.222.7a-b

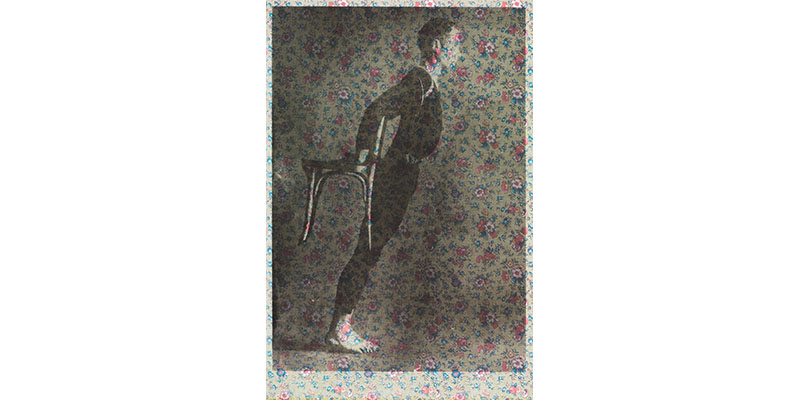

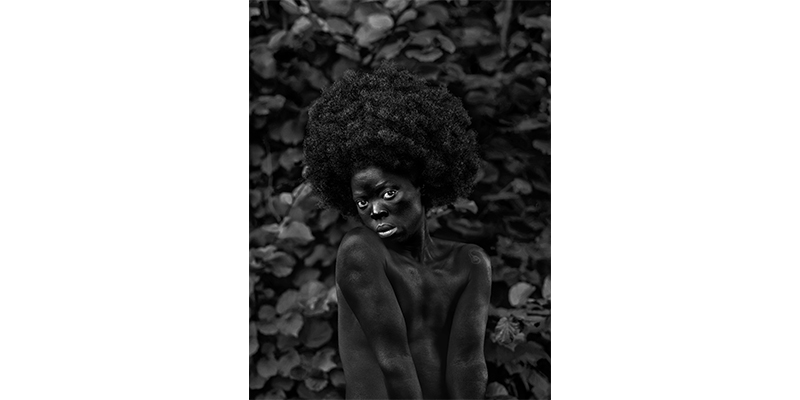

Refiloe Pitso, Daveyton, Johannesburg, Zanele Muholi, gelatin silver print, Museum Purchase: Carl Jacobs Foundation, © Zanele Muholi, 2017.70

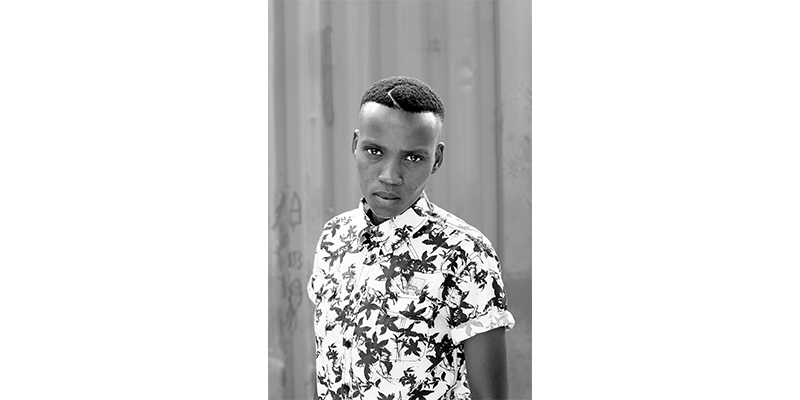

HeVi, Oslo, Zanele Muholi, gelatin silver print, Museum Purchase: Carl Jacobs Foundation, © Zanele Muholi, 2017.71

When I first decided to write a blog for Pride Month, I was very excited. I have worked in the museum field for 7 years now and have witnessed the challenges museums face in being inclusive. Historically, art museums were created as elitist institutions for kings and royalty to display their expensive art, collection of riches, and spoils from war. Today, art museums still get a bad rap and are constantly battling this image of being an exclusive organization meant only for the rich, white clientele. As someone who works in art museum education, I can tell you that it is a constant conversation amongst our staff about how we can be more inclusive to diverse audiences. I can also attest to the passion amongst my fellow staff-members to make sure we are welcoming to ALL PEOPLE, regardless of race, sexuality, gender identity, etc.

So when I had the idea to write a blog celebrating Pride Month, I was enthusiastic about the prospect of reaching a wider audience. I am white and cisgender, but I am a female who most closely identifies as pansexual, and I have many family members and friends who also identify within the LGBTQ+ acronym. I felt that my LGBTQ+ resume was solid and that taking on such an article would be easy. “I will write about the amazing LGBTQ+ artists in our collection!” I exclaimed to myself, “It will be great!” I decided that I would choose three LGBTQ+ artists from the collection, do a little research, regurgitate that research onto this blog, tell you where to find their work in the gallery and BAM! Inspiration and rainbows for all. But, as I began my research into the lives of these artists, it proved to be much more challenging than I had imagined.

In many cases, there was only speculation that an artist identified as LGBTQ+. In the case of Georgia O’Keeffe (b. 1887, d. 1986), an American painter known for her abstractions and large-scale paintings of flowers, many authors claim that she was bisexual. Others disagree and say that there is no evidence to prove this. I asked my fellow co-workers, thinking someone would have a clear-cut answer, but nobody could agree. I was torn. I wanted badly and proudly to exclaim, “Here is an iconic artist and guess what? She’s bisexual!” but with so many conflicting viewpoints, I was uncomfortable making that claim.

My dilemma did spark great conversation in my department, however, about the intricacies of sexuality and art history. For example, it is commonly believed that O’Keeffe’s flower paintings were actually close-ups of the female vulva. I was even taught this in my high school art class. In reality, O’Keeffe resisted the sexual readings into her paintings and often said she was not painting the female form. It is possible that this theory was first put forward by Alfred Stieglitz – the photographer and art dealer who later became O’Keeffe’s husband – and then further perpetuated by male art critics of the time. In short: sex sells.

In the same way, it is possible that, if O’Keeffe did identify as bisexual, it could have been written out of the historical record, as has happened many times throughout history. In a time when people could be ostracized, arrested, or institutionalized for their sexual orientation, it is easy to imagine why O’Keeffe may have wanted to keep this a secret. Perhaps we will never know and perhaps it doesn’t matter how she identified. What we do know about O’Keeffe is that her life, art, and even personal style have inspired many in the LGBTQ+ community. Her sharp, androgynous style – black tailored suits, collared shirts, and tennis shoes – suggest that she did not want to be seen through a gendered lens. This was the 1920s and ‘30s, after all, and the decision to dress “gender neutral” was revolutionary for the time. While O’Keeffe’s orientation might always remain mysterious, she continues to be an inspiration to people who feel they do not conform to strict gender roles.

Andy Warhol (b. 1928, d. 1987), on the other hand, was an easier artist to research. He was openly gay and considered by many a gay icon in the art world. Warhol was best known for his iconic pop art and his 1960s paintings of consumer products, such as Campbell’s soup cans and Coca-Cola. In the early 1950s, however, Warhol submitted works to an art show at the Tanager Gallery in New York City, but was rejected because the subject matter – two men embracing – was too openly gay. Remember, being gay was a crime in America in the 1950s, yet Warhol continued creating. His sexual identity often influenced his paintings, drawings and films throughout the rest of his career. In 1963, he opened up a studio in New York, known as “The Factory”, where he used silkscreens to mass produce images the same way corporations mass produced consumer goods. To increase production, Warhol enlisted the help of actors, performers, drag queens, socialites, and musicians who became known as the “Warhol Superstars.” The Factory was known as a place where people from the LGBTQ+ community could openly express themselves and create art.

Zanele Muholi (b. 1972) came up multiple times during my unofficial “Who is an LGBTQ+ Artist?” survey with my co-workers. Born in Umlazi, South Africa, Muholi is a photographer and filmmaker known for advocating on behalf of the LGBTQ+ community. According to an interview in Out Magazine, Muholi “[identifies] as a human being at this stage because of gender fluidity, and to avoid being confused by what the society expects out of us,” they say. “I came out as a same-gender loving person, but because there was no Zulu name for it, I was called a lesbian. But we move on, transpire, transgress, and transform in many ways; so I’m just human.” They have produced a number of photographic series’ investigating the ongoing bigotry and violence against LGBTQ+ people in South Africa. In their popular series, Faces and Phases (2006), Muholi photographed individual black-and-white portraits of lesbians, women, and transgender men, with frigid expressions that boldly confronts the gaze of each viewer. Today, Muholi, a self-proclaimed visual activist, continues to produce work and advocate for the LGBTQ+ community.

Personally, these artists have inspired me, not only because of their amazing work, but because of the journey they took me on when writing this article. When I set out to write this, I thought it would be a simple, cut-and-dry process of picking LGBTQ+ artists out of a box. But, obviously, people do not often fit into a box. History, art, gender and sexuality are all complex, but that’s the beauty that makes us human.

Must-See Art Works:

Georgia O’Keeffe, My Back Yard (1943), Gallery 211.

Andy Warhol, Pete Rose (1985) and Soup Can (Cream of Mushroom) (1962), Gallery 230.

Zanele Muholi, not currently on view, but you can view some of her photographs above.

Related Blog Posts

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

The Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the generosity of tens of thousands of contributors to the ArtsWave Community Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: