- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Audio Tour

Audio Tour

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

-

Art

- Art Home

- Exhibitions

-

Explore the Collection

- Explore the Collection Home

- African Art

- American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Contemporary

- Decorative Arts and Design

- East Asian Art

- European Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

- Fashion Arts and Textiles

- Musical Instruments

- Indigenous American Art

- Photography

- Prints

- South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Baby Tours

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Choose Your Own Gallery Adventure

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Blog

- Shop

Introduction

Kara Walker (b. 1969, Stockton, CA) is best known for her groundbreaking large-scale silhouette tableaux. Inspired by history, literature, mythology, art history, and fantasy, these works engage racial stereotypes to address slavery, racism, exploitation, gender, physical and sexual abuse, and imperialism. Her hard-hitting, unorthodox depictions of uncomfortable subjects expose systems of injustice and the raw flesh of generational wounds still in the process of healing. Walker’s work invites us to lean into our discomforts, our difficult questions and, perhaps, into our radical imaginations–the place within that holds the possibility to shape a new future.

A career-spanning exhibition, Kara Walker: Cut to the Quick features more than 80 works created between 1994 and 2019 from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation. This exhibition was first organized by the Frist Art Museum before traveling to Cincinnati. The labels throughout these galleries are going to call on you, the visitor, to rethink and re-examine your own histories and biases through a series of questions that prompt reflection. We encourage you to take the time to consider the imagery and meaning Walker explores–there are no easy answers to be found. We understand that the works on view are complex, unsettling, and possibly triggering.

We offer the Community Care Space as a safe place to reconnect with the rhythm of your breathing, rest, and reflect.

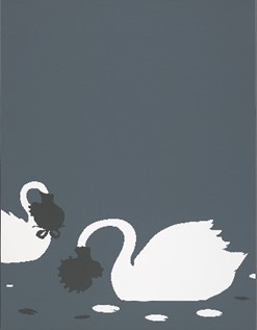

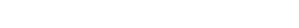

1: “Bird Of Freedom / Whereas the Negress Can Fly”

1 en español: “Pajaro”

2: THE EMANCIPATION APPROXIMATION

3: THE EMANCIPATION APPROXIMATION Part 2

Porgy and Bess

The 1935 opera Porgy and Bess is set in 1920s Charleston, South Carolina, to music by George Gershwin with a libretto by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Porgy, a disabled beggar, tries to free the beautiful Bess from her manipulative lover, Crown, and the drug dealer Sportin’ Life. The operatic tragedy was criticized almost from the beginning for its characterization of the lifestyle of poor African Americans and its use of their dialect, as imagined by white authors. While observing rehearsals for a 2011 performance, Kara Walker made sketches “to understand the music and to allow [herself] to get caught up in the fantasy of theater.”

Later, Walker created sixteen original lithographs to illustrate a 2013 publication of the libretto by Arion Press. She also produced four companion lithographs not included in the book. Lithography is well suited to the expressiveness of Walker’s smudges, rubbings, and loose, broad strokes. The artist says of the characters, “They’ve become archetypes of another no less grand drama, that of: ‘American Negroes’ drawn up by white authors, and retooled by individual actors, amid charges of racism, and counter charges of high art on stage and screen, in the face of social and political upheaval, over generations.”

Race and Representation

The earliest and most recent works in this exhibition underscore how negative stereotypes reinforce the prejudice and discrimination that limit access to education, employment, property and voting rights, social mobility, and equitable access to generational wealth and power.

Walker shocked the art world in the 1990s with cut-paper silhouettes constructed from the racist imagery of “Sambo art,” problematic caricatures of Black bodies with exaggerated physiognomy popular during the nineteenth century. The full lips, bug eyes, and wiry hair that define Topsy (1994), the character of an enslaved girl in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), put a racist caricature on full display in a fine art context. Stowe, intending to be empathetic, ultimately created a characterization of otherness based on race that endured through the Civil War, during Jim Crow, segregation, the civil rights era, and beyond. Such problematic representations still dominate, both consciously, and unconsciously, societal thought and influence practices that uphold this country’s racial hierarchy. The descendants of formerly enslaved workers continued to receive little of the wealth they created with subsequent farm labor systems such as sharecropping, tenant farming, and the forced servitude still practiced in some prisons today.

4: RESURRECTION STORY WITH PATRONS

5: VANISHING ACT

6: “A Slave Ship Gets Nowhere without The Sea to Carry It”

6 en español: “El Barco (A Slave Ship Gets Nowhere)”

7: FONS AMERICANUS

8: BURNING AFRICAN VILLAGE PLAY SET WITH BIG HOUSE AND LYNCHING

The Civil War

Between 1861 and 1865, Harper’s Weekly reported contemporaneous accounts of Civil War battles and political developments, largely supporting Lincoln and the federal government. In 1894, the weekly published one thousand illustrations of battlefields, maps, plans, and likenesses of military figures in Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War, by Alfred H. Guernsey and Henry M. Alden.

In 2005, Kara Walker superimposed her signature silhouettes over large-scale prints from this pictorial history. The Harper’s Weekly images had been intentionally inoffensive to a Southern white readership. While Walker’s flat, opaque figures insistently interject a conspicuously absent African- American point of view. Silhouettes obfuscate the original intention while forcing the viewer to contend with the unreliability of history. Who is telling the story? Whose history is included, and whose is omitted? Who is validated, and who is obliterated?

9: “Silhouette”

9 en español: “Silueta”

10: PASTORAL

Ocean Way Recording Studios donated recording time and professional expertise to produce this audio tour.

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

The Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the generosity of tens of thousands of contributors to the ArtsWave Community Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: