Introduction

I’m Peter Bell, the museum’s Curator of European Paintings, Sculpture, and Drawings. I am reading the introduction for Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism explores the intersections of art, gastronomy, and national identity in France in the late 1800s. The exhibition showcases more than 60 paintings and sculptures, including the work of Jules Dalou, Victor Gilbert, Paul Gauguin, Eva Gonzalès, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Vincent van Gogh—artists who examined the nation’s unique relationship with food. The bounty of France’s agriculture and its chefs' skill had long helped define its strength and position on the international stage. This self-image as the world’s culinary capital became more important in the late nineteenth century as the country grappled with war, political instability, imperialism, and industrialization. In this climate, France’s culinary traditions signaled notions of its refinement, fortitude, and ingenuity while exposing fractures destabilizing national identity. From cultivation to consumption, food was central to notions of glory but also those of collective pain. Farm to Table puts this history on view through the eyes and hands of the period's greatest artists, who avidly brought subjects from agricultural fields to Parisian dining rooms into their works, documenting and reinforcing monumental cultural shifts at the heart of European modernity.

Privation

I’m Peter Bell, the museum’s Curator of European Paintings, Sculpture, and Drawings. I am reading the "Privation" section in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

The historical context of Farm to Table begins with the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). France’s defeat by the German armies was an embarrassing military failure with seismic sociopolitical implications that included widespread food shortages and the collapse of Napoleon III’s Second Empire. To make matters worse, in the spring of 1871, the working-class Parisians who defended the city during the siege took up arms against the newly established Third Republic. This civil insurgency, known as the Paris Commune, led to further bloodshed, and it took two months for the French Army to suppress the movement and its tens of thousands of supporters.

Consequently, citizens of all socio-economic positions faced rebuilding a nation that was severely depleted of resources, and a sense of incendiary unease lingered over the urban working class for the next two decades. Ultimately, the French people persevered through this post-war privation. The artworks in this section suggest tensions surrounding subsistence at the individual and collective level.

Girl Eating Porridge

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (French, 1825–1905), Girl Eating Porridge, 1874, oil on canvas, Cincinnati Art Museum, Bequeathed by Reuben R. Springer, 1884.335

Description

I’m Peter Bell, the museum’s Curator of European Paintings, Sculpture, and Drawings. I am reading the description of the Girl Eating Porridge in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Girl Eating Porridge is an oil on canvas painting by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, a French artist who lived from 1825 to 1905. It was painted in 1874 and bequeathed to the Cincinnati Art Museum by Rueben R. Springer. The registration number is 1884.335.

Girl Eating Porridge is a vertically oriented painting measuring 38 and one-half by 24 and one-half inches. A young white girl, about 10 years old, sits on a small wooden bench eating a bowl of porridge. She turns her body to the left and looks over her left shoulder directly at the viewer. The girl has light brown curly hair pulled back from her rosy, cherub-like face with a navy-blue ribbon. She has a slight smile, enough that the dimples on her cheeks are apparent. She wears a white blouse with wide sleeves that reach just to her wrists. Over this is a dress with wide black straps and a dark green skirt. She is barefoot, only her left foot visible. She holds a brown ceramic bowl in her left hand, resting it on her knees. In her right hand, she has a metal spoon, about to be raised to her mouth. The setting for this painting is a kitchen space with smooth stone walls.

Label

I’m Peter Bell, the museum’s Curator of European Paintings, Sculpture, and Drawings. I am reading the label for the Girl Eating Porridge in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Girl Eating Porridge is an oil on canvas painting by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, a French artist who lived from 1825 to 1905. It was painted in 1874 and bequeathed to the Cincinnati Art Museum by Rueben R. Springer. The registration number is 1884.335.

Idealized depictions of French peasants and country folk were among William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s most popular works. His paintings of children, such as this girl eating porridge from a common earthenware bowl, convey a sense of purity and contentment. The simplicity of the setting, from the lack of a table to the cabbage and onion peels on the ground, suggests that she may be a domestic worker.

Bouguereau was one of the most admired artists of the late nineteenth century. Critics, artists, and the public flocked each year to the Paris Salon to see his latest creations; collectors in Europe and America vied to acquire his paintings, often paying astronomical prices. He was a superb draftsman and staunch defender of traditional painting techniques and subject matter in the face of the Impressionists' radically “modern” approach to painting.

A Rat Seller During the Siege of Paris in 1870 Artwork

Narcisse Chaillou (French, 1835–1916), A Rat Seller During the Siege of Paris in 1870, 1871, oil on canvas, Sheffield Museums, VS 1395

Description

I’m Peter Bell, the museum’s Curator of European Paintings, Sculpture, and Drawings. I am reading the description of A Rat Seller During the Siege of Paris in 1870 in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

A Rat Seller During the Siege of Paris in 1870 is an oil on canvas painting by Narcisse Chaillou, a French artist who lived from 1835 to 1916. It was painted in 1871. It is in the Sheffield Museums Collection, and its registration number is VS 1395.

A Rat Seller During the Siege of Paris in 1870 is a vertically oriented painting measuring 32 and thirteen-sixteenths by 27 and thirteen-sixteenths by three and three-eighths inches. A teenage boy stands in an alley space with posters in French hanging on the brown masonry wall behind him. He wears a white chef’s hat on top of his sandy brown hair that peaks out on his forehead. He is looking down at his left arm, concentrating on rolling up his white shirt cuff with his right hand. This cuff is apparent under his long-sleeved navy-blue coat with red trim. Over this, he wears a long white apron with a splattering of red blood at thigh level. This protects his dark trousers, also stained with blood. He wears a brown leather glove holding a large knife in his left hand. In front of him, sitting on a kitchen chair draped in a green apron, its ties wrapped around the seat back, is a wooden chopping block upon which sits a dead brown rat skewered with a white handled knife, about to be butchered. Another, already processed rat, is nailed to the back of the chair. A small French flag sticks out of the back of the chair.

Label

I’m Peter Bell, the museum’s Curator of European Paintings, Sculpture, and Drawings. I am reading the label for A Rat Seller During the Siege of Paris in 1870 in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

A Rat Seller During the Siege of Paris in 1870 is an oil on canvas painting by Narcisse Chaillou, a French artist who lived from 1835 to 1916. It was painted in 1871. It is in the Sheffield Museums Collection, and its registration number is VS 1395.

Dressed in the blue, white, and red of France’s flag, Narcisse Chaillou’s young butcher embodies French culinary nationalism amid the food shortages of the Prussian siege. Rats became a wartime commodity for citizens who could not afford pricier meats. Despite the desperation of the moment, Chaillou’s butcher stands proud, smiling as he rolls up his sleeve to preside over a makeshift counter. He appears to relish preparing the rodent in the style of a side of beef for his future customers. A small French flag waves from the back of the chair—an icon of hope and fortitude for the nation. Exhibited at the Salon of 1872, the painting was a public favorite.

The Fields

I’m Karen Goins, the museum’s finance and human resources coordinator. I am reading the "The Fields" section in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Prior to the 1800s, the rural laboring class suffered considerable social stigma. This began to change as the century progressed, and the economic, social, and political conflicts within France gave rise to a different kind of ‘peasant.’ This ideal rural worker could become peaceful, literate, and secularized with the help of the state—in short, become the repository of French values—and provide a bulwark against the radical urban working class. Unlike city workers, who were often seen as threats to the republic in the wake of the 1871 Paris Commune (a violent urban uprising), these rural workers could at once signal the grandeur of France’s agrarian traditions and herald a future of economic advancement and political agency.

The artworks in this section reveal the backbreaking labor of rural workers, whose efforts were at the foundation of France’s food supply. Central to these paintings are the agricultural products of wheat, oats, and barley, essential in creating the country’s crusty baguettes, rustic pain de campagne, flakey croissants, and pillowy brioches.

Harvest Scene

Daniel Ridgway Knight (American, 1839–1924), Harvest Scene, 1875, oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.2118

Description

I’m Karen Goins, the museum’s finance and human resources coordinator. I am reading the description of the Harvest Scene in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Harvest Scene is an 1875 oil on canvas painting by Daniel Ridgeway Knight, an American artist who lived from 1839 to 1924. It is in the Chrysler Museum of Art collection and was a gift from Walter P. Chrysler. The registration number is 71.2118.

Harvest Scene is a horizontally oriented painting measuring 49 and one-quarter by 69 and one-quarter by four and three-eighths inches. In this expansive scene, two groups of farm workers take a break from harvesting wheat. The entirety of the landscape on which they rest is the warm gold of grain. In the foreground and to the left of the painting, scrubby green plants and red wildflowers are present. Moving from the foreground to the background, the first figure the viewer encounters is a toddler, dressed in a red shirt and dark blue pinafore, asleep under a blue umbrella in the center left of the painting. Moving into the midground and to the right of center, a large group of women, of all ages, a young boy, and an older man sit in a circle, rest on a haystack, or stand behind the group. They are all dressed in worn clothing in faded shades of blue, purple, red, and brown. All the women wear full aprons and caps, kerchiefs, or bonnets on their heads. The man wears a blue cap over his white hair. Moving the next group, to the left of center and a bit further back than the previously described group, is a small circle of workers dressed in the same style and muted colors. Behind this group and to their right, two men lean on scythes, facing each other, talking. Scattered around both groups and receding into the background are large circular haystacks. In the background there are green trees and a village off to the left. The sky takes up almost half of this picture. It is light blue, nearly gray with wispy white clouds.

Label

I’m Karen Goins, the museum’s finance and human resources coordinator. I am reading the label for the Harvest Scene in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Harvest Scene is an 1875 oil on canvas painting by Daniel Ridgeway Knight, an American artist who lived from 1839 to 1924. It is in the Chrysler Museum of Art collection and was a gift from Walter P. Chrysler. The registration number is 71.2118.

Daniel Ridgway Knight studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts from 1858 to 1861, and then in Paris until 1863. He returned to the United States to serve in the army during the Civil War but then returned to France in 1872, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Inspired by Barbizon School painters, Knight specialized in meticulously rendered and warmly illuminated rural views of working people. In Harvest Scene, he idealizes the lives of multiple generations of peasants enjoying a meal together on a break from the hard work of harvesting and stacking hay.

The Haystack

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926), The Haystack, 1891, oil on canvas, Private collection

Description

I’m Karen Goins, the museum’s finance and human resources coordinator. I am reading the description of The Haystack in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Claude Monet, a French artist who lived from 1840 to 1926, painted the oil on canvas, The Haystack in 1891. It is in a private collection.

The Haystack is a horizontally oriented painting measuring 34 and five-eighths by 45 and one-quarter by four-and-three-quarters inches. The colors of a sunset—dark green and muted reds, oranges, pinks, and yellows—create the palette for this simple landscape painting. Here, Monet captures a wheat field after harvest, a lone circular haystack with a pointed top in the foreground and left of center, the focal point. The light source is waning, as the sun sets behind the green hills that span the painting’s background, creating a blue shadow in front of the haystack. The expanse of the plowed field to the right of center is sun-dappled, creating a warm glow on the ground. The sky, taking up only a quarter of the background, is golden yellow where it meets the hills and shifts to a light blue as it reaches off the top of the canvas.

Label

I’m Karen Goins, the museum’s finance and human resources coordinator. I am reading the label for The Haystack in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Claude Monet, a French artist who lived from 1840 to 1926, painted the oil on canvas, The Haystack in 1891. It is in a private collection.

In the early 1890s, Claude Monet created a series of more than 20 paintings of haystacks (more correctly termed grainstacks) in the fields bordering his home in Giverny, depicting their architectural forms at various times of day and under different weather conditions.

Cereal grains (wheat, barley, oats) and the act of farming were of fundamental importance to French identity. Haystacks—agricultural “monuments” that speak both to the natural world and human society—were the first subject of Monet’s series paintings, which would later include poplars and Rouen Cathedral—all subjects related to French fortitude and longevity.

Saharan Dwelling, Biskra District, Algeria

Gustave Achille Guillaumet (French, 1840–1887), Saharan Dwelling, Biskra District, Algeria, 1882, oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter Chrysler, Jr., 71.655

Description

I’m Karen Goins, the museum’s finance and human resources coordinator. I am reading the description of Saharan Dwelling, Biskra District, Algeria, in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Saharan Dwelling, Biskra District, Algeria, from 1882, is an oil on canvas painting by Gustave Achille Guillaumet, a French artist who lived from 1840 to 1887. It is in the Chrysler Museum of Art collection and was a gift from Walter P. Chrysler. The registration number is 71.655

Saharan Dwelling, Biskra District, Algeria, is a sizeable horizontally oriented painting measuring 63 by 73 and five-eighths by three inches. The setting for this work is a high-ceilinged kitchen with clay walls and two parallel pillars left of center, one in the foreground and the other further back in the composition. Between the two columns, in the midground, a child, dressed in a floor-length blue tunic, crouches down to milk a sheep. To the right, in the lower corner, two men sit, one on the ground and another on a short wall. The one on the ground sits with his left leg tucked beneath him and his right leg stretched out. He has a round metal vessel with a flat top in front of him. He holds a stick in his stretched-out right arm. He wears a similar blue tunic to that of the child. He has a white turban wrapped around his head. Behind him, a younger man sits on a short wall. He wears a red gown under a dark blue cape; his attire also includes a dark blue turban. Moving into the background, we encounter a small, speckled cat, a tall container holding what appears to be tall reeds or branches, and in the very back, a staircase leads to a sun-drenched exterior. The small face of a man peeks into the interior space. Scattered around the room are implements common to a kitchen—a basket of eggs, and various vessels, some holding grain. A slight glow comes from the left of the painting where an open hearth is only just visible.

Label

I’m Karen Goins, the museum’s finance and human resources coordinator. I am reading the label for Saharan Dwelling, Biskra District, Algeria in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Saharan Dwelling, Biskra District, Algeria, from 1882, is an oil on canvas painting by Gustave Achille Guillaumet, a French artist who lived from 1840 to 1887. It is in the Chrysler Museum of Art collection and was a gift from Walter P. Chrysler. The registration number is 71.655

As had generations of French artists before him, Gustave Achille Guillaumet visited North Africa to find “exotic” subject matter that was popular among his European audiences. In this painting, Guillaumet portrays the daily kitchen routines of a rural home in Algeria’s Biskra District on the northern edge of the Sahara Desert.

In an environment of dusty light and deep, cool shadows, family members work together in the kitchen, grinding grains and milking a sheep. Stairs leading upward toward bright daylight suggest that much of the clay-walled, high-ceilinged home is below ground level, a necessary means of temperature regulation in the desert climate. Though the household activities shown here would be familiar to French audiences, the Algerian setting gave them an alternative view of agrarian life.

At Pasture

I’m Alexa Ramirez, the museum’s school programs coordinator. I am reading the "At Pasture" section in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Pasture is an Old French word that denotes fields suitable for grazing. In the mid-19th century, after years of instability in France, its pastures symbolized the nation’s potential growth. The authors of the paintings in this section championed shepherds not only as the caretakers of French livestock and the soil and fields that sustained them but also as stewards of the nation, their labor providing sustenance for its people. Regions and locales such as Barbizon, Le Havre, and Le Hague inspired an entire generation of painters who sought to elevate the genre of landscape in the eyes of the public. Their works also often helped advocate for the working classes living in the rural parts of France often overlooked by the bourgeois (middle-class) and ruling classes concentrated in cities.

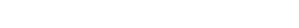

Road by the Mill

Theodore Robinson (American, 1852-1896), Road by the Mill, 1892, oil on canvas, Cincinnati Art Museum, Gift of Alfred T., and Eugenia I. Goshorn, 1924.70

Description

I’m Alexa Ramirez, the museum’s school programs coordinator. I am reading the description of the Road by the Mill in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Theodore Robinson, an American artist who lived from 1852 to 1896, painted Road by the Mill in 1892. It is an oil on canvas painting in the Cincinnati Art Museum collection, a gift from Alfred T. and Eugenia I. Goshorn. The registration number is 1924.70.

Road by the Mill is a horizontally oriented landscape painting measuring 20 by 25 and three-sixteenths inches. In this bucolic scene of the French countryside, a large three-story white masonry mill with a red roof encompasses the midground to the left of center. Additional white structures with brown roofs are clustered across the remainder of the midground. Trees are interspersed around these buildings. Stretching up and into the background are green hills serving as farmland. Coming out of this small village is a curving road that meanders into the foreground. Along the left side of the road is a large wooden fence, likely used to keep animals in. A teenage girl in a blue dress and white apron walks along this road. She walks behind and to the right of a large brown and white cow as if leading it to a pasture. The ground on either side of this dirt road is green grass. The sky above this scene is light blue with only a few white clouds.

Label

I’m Alexa Ramirez, the museum’s school programs coordinator. I am reading the label for the Road by the Mill in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Theodore Robinson, an American artist who lived from 1852 to 1896, painted Road by the Mill in 1892. It is an oil on canvas painting in the Cincinnati Art Museum collection, a gift from Alfred T. and Eugenia I. Goshorn. The registration number is 1924.70.

After studying in Chicago and New York, Theodore Robinson continued his training in Paris in the late 1870s, studying alongside fellow American John Singer Sargent. On his second extended stay in France, which began in 1884, he became involved with the Giverny artist colony. A close friend of Claude Monet, Robinson’s painting style was influenced by the Impressionists' lighter palette, loose brushwork, and attention to light effects. Robinson made this painting in 1892, just before he returned to the United States.

Shepherd and Sheep

Anton Mauve (Dutch, 1838-1888), Shepherd and Sheep, circa 1880, oil on canvas, Cincinnati Art Museum, Bequest of Mary Hanna, 1956.117

Description

I’m Alexa Ramirez, the museum’s school programs coordinator. I am reading the description of Shepherd and Sheep in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Shepard and Sheep is a circa 1880 oil on canvas painting by Anton Mauve, a Dutch artist who lived from 1838 to 1888. It is in the Cincinnati Art Museum collection as a bequest from Mary Hanna. The registration number is 1956.117.

Shepard and Sheep is a horizontally oriented painting measuring 24 by 34 inches. A stormy sky and thick gray clouds threaten a flock of sheep and their shepherd. Moving away from the center foreground and into the background, a man, visible from behind, walks behind a large flock of white sheep, also seen from behind. He wears a dark brown coat, pants, a black cap, and sturdy work boots. A black herding dog walks to his left and a bit behind him. The land around them is muted green with hints of brown and yellow. The dirt path upon which they walk is well-worn. The artist's signature, A. Mauve, is in the lower right corner of the painting.

Label

I’m Alexa Ramirez, the museum’s school programs coordinator. I am reading the label for Shepherd and Sheep in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Shepherd and Sheep is a circa 1880 oil on canvas painting by Anton Mauve, a Dutch artist who lived from 1838 to 1888. It is in the Cincinnati Art Museum collection as a bequest from Mary Hanna. The registration number is 1956.117.

Anton Mauve was known for his depictions of farm life, particularly sheep herding. In this painting, he captures the flock from a unique point of view, showing the shepherd, his dog, and the sheep walking away from the viewer. With soft, lyrical brushstrokes, he captured the hazy light of the early evening as it plays across the backs of the animals.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, The Hague became the center of a major school of landscape painting. Inspired by Barbizon School artists such as Jean-François Millet, whose work could be seen in art galleries in the Netherlands, Dutch artists like Mauve recorded the gray skies, flat terrain, and simple peasant life of their native country.

Bounty of the Sea

I’m Maggie Komp, a server in the museum’s Terrace Cafe. I am reading the "Bounty of the Sea" section in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

As early as 1830, the steam-powered engine began to transform maritime battles and trade throughout Europe. French ports such as Trouville started to grow, increasing the importance of the maritime provinces of Brittany, Normandy, and Provence. Steamboats allowed for longer trips and larger hauls, providing goods to support the rising populations of French cities. The islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, along the southwestern coast of Newfoundland and Labrador (a province in modern-day Canada), also contributed to France’s sea trade. Imports and fishing bounties traveled from France’s northwestern and southern coasts through its extensive river network to provide city markets, such as Les Halles in Paris, with fresh seafood and international trade goods. This section's artworks capture the fishing industry's tools and markets and showcase the more obscure laborers, such as worm and snail gatherers.

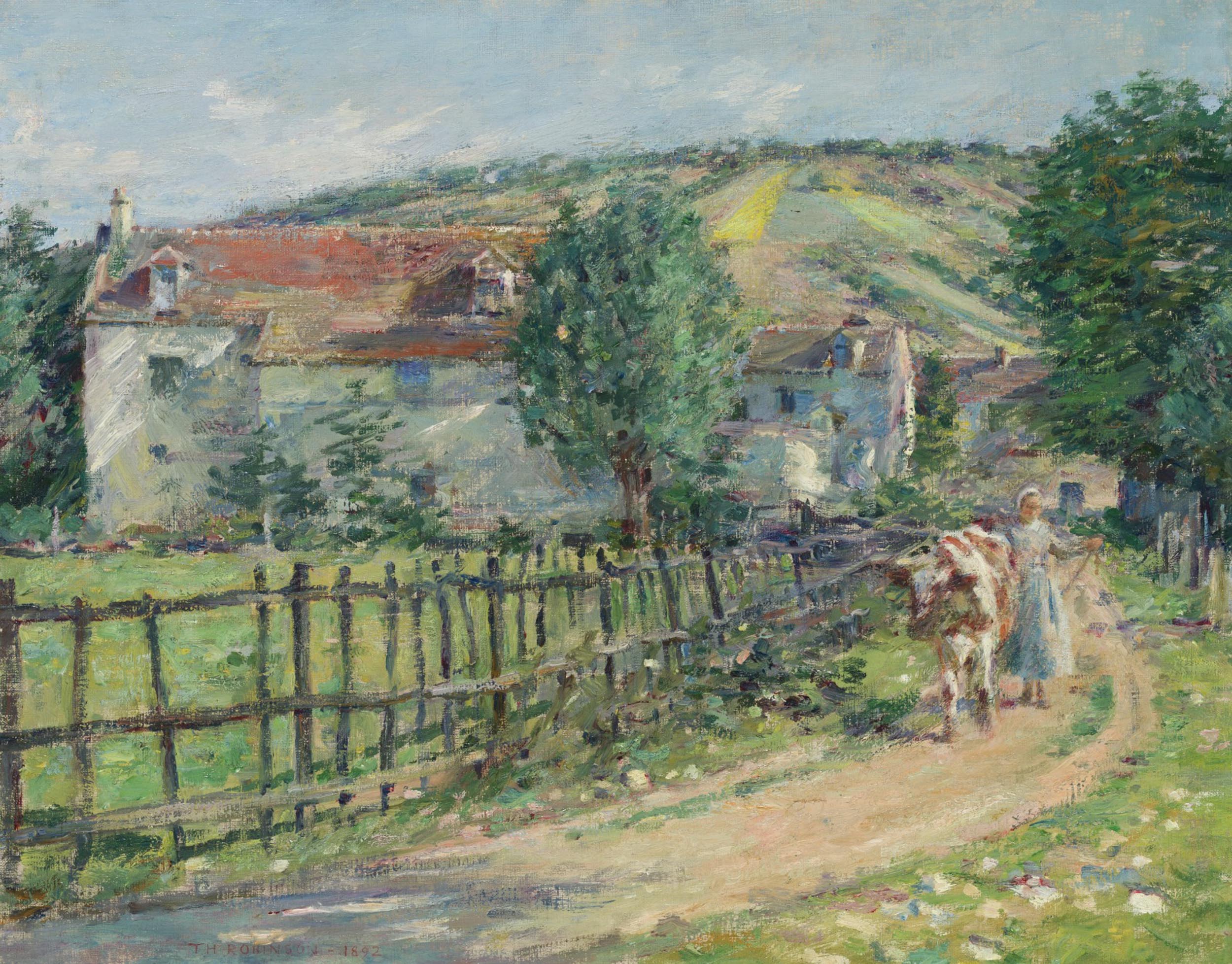

Red Mullets

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), Red Mullets, c. 1870, oil on canvas, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Friends of the Fogg Art Museum Fund

Description

I’m Maggie Komp, a server in the museum’s Terrace Cafe. I am reading the description of Red Mullets in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Claude Monet, a French artist who lived from 1840 to 1926, painted Red Mullets in oil on canvas around 1870. It is in the Harvard Art Museums, Fogg Museum collection, courtesy of the Friends of the Fogg Art Museum Fund.

Red Mullets is a horizontally oriented still life painting measuring 21 by 26 and three-quarters by two and five-eighths inches. Monet captures the forms of two red mullet fish resting on a crumpled white cloth in this picture. The mullets lay side by side, one with its head pointed into the foreground, the other to the background. They both have silvery-white scales with hints of peachy red speckles throughout. Their feathery tails are light orange. The fish and cloth sit on a light brown surface. The artist’s name, Claude Monet, is written in the lower right corner.

Label

I’m Maggie Komp, a server in the museum’s Terrace Cafe. I am reading the label for Red Mullets in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Claude Monet, a French artist who lived from 1840 to 1926, painted Red Mullets in oil on canvas around 1870. It is in the Harvard Art Museums, Fogg Museum collection, courtesy of the Friends of the Fogg Art Museum Fund.

Atop a conch shell-shaped napkin, these two red mullets appear to be fresh from the market. Sourced from the Mediterranean Sea and Northern Atlantic, these relatively small fish became a common ingredient in French cuisine in this period. Claude Monet painted the mullet’s scales in a frenzy of peach and white brushstrokes and chose to display the fish prior to it being filleted. However, the high vantage point suggests that a chef is about to prepare them for consumption. Heavily influenced by the Spanish and Dutch genre traditions, Monet often cropped his still lifes closely, placing their subjects centrally on the canvas.

Trouville

Eugène Boudin (French, 1824–1898), Trouville, 1891, oil on canvas, Cincinnati Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 1957.214

Description

I’m Maggie Komp, a server in the museum’s Terrace Cafe. I am reading the description of Trouville in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Trouville is an 1891 oil on canvas painting by Eugène Boudin, a French artist who lived from 1824 to 1898. It is in the Cincinnati Art Museum collection and was a museum purchase. The registration number is 1957.214.

Trouville is a small horizontally oriented landscape painting measuring 15 and three-eighths by 21 and three-eighths inches. The small seaside village of Trouville is depicted in this picture. Here, the artist paints a scene of a small bay in the midground stretching from the right side of the canvas to just left of center. In the foreground and to the left, brownish green land wraps around the harbor, and six unoccupied fishing boats fill the space. A solitary man stands amongst the vessels. Stretching from the left background, and to the right, we first encounter a man and a woman, the latter holding a parasol over her head, leaning on a wood fence, looking into the cove, the larger sea behind them. Continuing from left to right across the canvas, the artist includes the village’s buildings and docks. On the right, what appears to be a fort-like structure is visible. Several sailboats with white sails are moored in the cove at the pier. A fishing boat containing two men floats in the middle of the harbor. The sky above the scene is light blue with white clouds touched with gray to create shadows.

Label

I’m Maggie Komp, a server in the museum’s Terrace Cafe. I am reading the label for Trouville in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Trouville is an 1891 oil on canvas painting by Eugène Boudin, a French artist who lived from 1824 to 1898. It is in the Cincinnati Art Museum collection and was a museum purchase. The registration number is 1957.214.

Born in Honfleur, Eugène Boudin was a native of the northern coast of France, a frequent subject of his canvases. Boudin’s handling of the effects of light and water made him a favorite among artists now associated with the Impressionists. This work encapsulates Boudin’s move towards Impressionist brushwork near the end of his career.

In this scene, Boudin documents Trouville, a port city in Normandy that became a popular tourist destination in the nineteenth century. Boudin often painted the city, depicting its beachgoers and fishermen with equal importance. Here, Boudin cleverly contrasts the fishing vessels in the foreground with the boats of leisure servicing tourists seen in the distance.

Charger

Barbizet Studio (c 1850-1890) attributed manufactory, Charger, circa 1889, glazed ceramic, Cincinnati Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. J. Louis Ransohoff, 1923.943

Description

I’m Maggie Komp, a server in the museum’s Terrace Cafe. I am reading the description of the Charger in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

The Barbizet Studio, active from 1850 to 1890, is the attributed manufacturer of this glazed ceramic Charger from around 1889. It is in the Cincinnati Art Museum collection and was a gift from Mrs. J. Louis Ransohoff. The registration number is 1923.943.

This large Charger (or platter) is a three-dimensional form measuring four and three-quarters inches in height and 25 and one-quarter inches in diameter. This platter depicts flora and fauna that reside in or near water. A shallow vessel, the entirety of the black, wide, wavy-edged inside rim is decorated with various creatures and plants, including a gray snake with black spots slithering around the edge, a turtle, another coiled gray snake, a snail, a lizard, and various shells, ferns, and leaves. In the center of the charger is a large brown crab sitting on a light mossy-green surface that is rippled to resemble water. Between its claws is a small spiral shell.

Label

I’m Maggie Komp, a server in the museum’s Terrace Cafe. I am reading the label for the Charger in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

The Barbizet Studio, active from 1850 to 1890, is the attributed manufacturer of this glazed ceramic Charger (or platter) from around 1889. It is in the Cincinnati Art Museum collection and was a gift from Mrs. J. Louis Ransohoff. The registration number is 1923.943.

To produce the variety of lifelike, three-dimensional animals decorating the surface of this charger, or large plate, the artist made plaster molds directly from the creatures he sought to recreate and cast them in clay. The term Palissy ware refers to this realistic style featuring brightly colored lead-based glazes, as they imitate the work of the French Renaissance potter Bernard Palissy (1510–1589). Victor Barbizet (circa 1805–circa 1870) is credited with establishing the mass production of this type of rustic ware in Paris in the nineteenth century.

Garden and Grove

I’m Charlotte Ogorek, the museum’s Rexroth project assistant. I am reading the "Garden and Grove" section in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

By the mid-nineteenth century, growing populations in French cities—Paris especially—forced many residents out of the city centers and into the suburbs. This population movement prompted new construction projects for gardens and orchards that could support the demand for food production, resulting in small-scale agricultural developments that nestled between homes and other buildings just outside the city. The paintings in this section provide a glimpse of these changes, as artists were eager to document the convergence of rural and urban environs.

The Gardener–Old Peasant with Cabbage

Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), The Gardener–Old Peasant with Cabbage, 1883–95, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1994.59.6

Description

I’m Charlotte Ogorek, the museum’s Rexroth project assistant. I am reading the description of The Gardener–Old Peasant with Cabbage in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

The Gardener–Old Peasant with Cabbage from 1883 to 1895 is an oil on canvas painting by Camille Pissarro, a French artist who lived from 1830 to 1903. It is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and part of the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon. The registration number is 1994.59.6.

The Gardener–Old Peasant with Cabbage is a vertically oriented painting measuring 42 by 35 and five-eighths by three and three-quarters inches. Here, a man, perhaps in his late 50s or early 60s, stands to the right of center, taking up three-quarters of the painting. He wears a white shirt over which a brown vest with black trim is apparent. He has a blue apron hanging around his neck and reaching past his waist. He wears a brown cap with a short bill, of which gray hair peaks out at the temples and nape. The old gardener has the ruddy appearance of someone who spends their days outdoors. He looks down at the green cabbage he holds in his hands. Stacks of additional cabbages are visible behind him and in front of him.

Label

I’m Charlotte Ogorek, the museum’s Rexroth project assistant. I am reading the label for The Gardener–Old Peasant with Cabbage in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

The Gardener–Old Peasant with Cabbage from 1883 to 1895 is an oil on canvas painting by Camille Pissarro, a French artist who lived from 1830 to 1903. It is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and part of the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon. The registration number is 1994.59.6.

An older man with ruddy skin clutches a cabbage, trimming its outer leaves. Piled high behind him, a mound of the leafy vegetables acts as a backdrop for the gardener’s portrait. Fringes of gray hair sprout from under his peanut-brown hat, and his jaw falls slack as he focuses on his task.

This was a profoundly personal painting for Camille Pissarro, as critics once deridingly labeled him as a specialist of cabbage paintings. His repeated depictions of the humble vegetable, a common fixture in the diets of the poor, evoke his empathy for the working class, who suffered economically under the Third Republic’s industrialization. Therefore, Pissarro’s frequent representation of the lower classes amongst the vegetables was often contentious with upper-middle class audiences.

Apple Trees in Flower

Alfred Sisley (French, 1839–1899), Apple Trees in Flower, 1880, oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 77.412

Description

I’m Charlotte Ogorek, the museum’s Rexroth project assistant. I am reading the description of Apple Trees in Flower in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Apple Trees in Flower from 1880 is an oil on canvas painting by Alfred Sisley, a French artist who lived from 1839 to 1899. It is in the Chrysler Museum of Art collection and was a gift from Walter P. Chrysler. The registration number is 77.412

Apple Trees in Flower is a horizontally oriented landscape painting measuring 36 by 41 and three-quarters by three and five-eighths inches. Bright cobalt blue skies with a whisper of white clouds provide a backdrop for an orchard of white flowering apple trees. In the foreground, three trees are painted in detail, their bark, branches, and flowers clearly depicted. The trees become more impressionistic as the scene recedes into the background. The ground is green, pink, and blue, created by the trees' shade. On the left, two figures, a man and a woman, stand amongst the trees. The woman holds a basket in front of her.

Label

I’m Charlotte Ogorek, the museum’s Rexroth project assistant. I am reading the label for Apple Trees in Flower in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Apple Trees in Flower from 1880 is an oil on canvas painting by Alfred Sisley, a French artist who lived from 1839 to 1899. It is in the Chrysler Museum of Art collection and was a gift from Walter P. Chrysler. The registration number is 77.412

In 1880, Sisley settled near the forests of Fontainebleau, a region southeast of Paris with a long history of en plein air (outdoor) painting. Apples, a common fruit in France, were available for harvest from late summer through autumn and in multiple provinces. Here, Sisley has chosen to show the trees in bloom, capturing the natural beauty of the French countryside in spring.

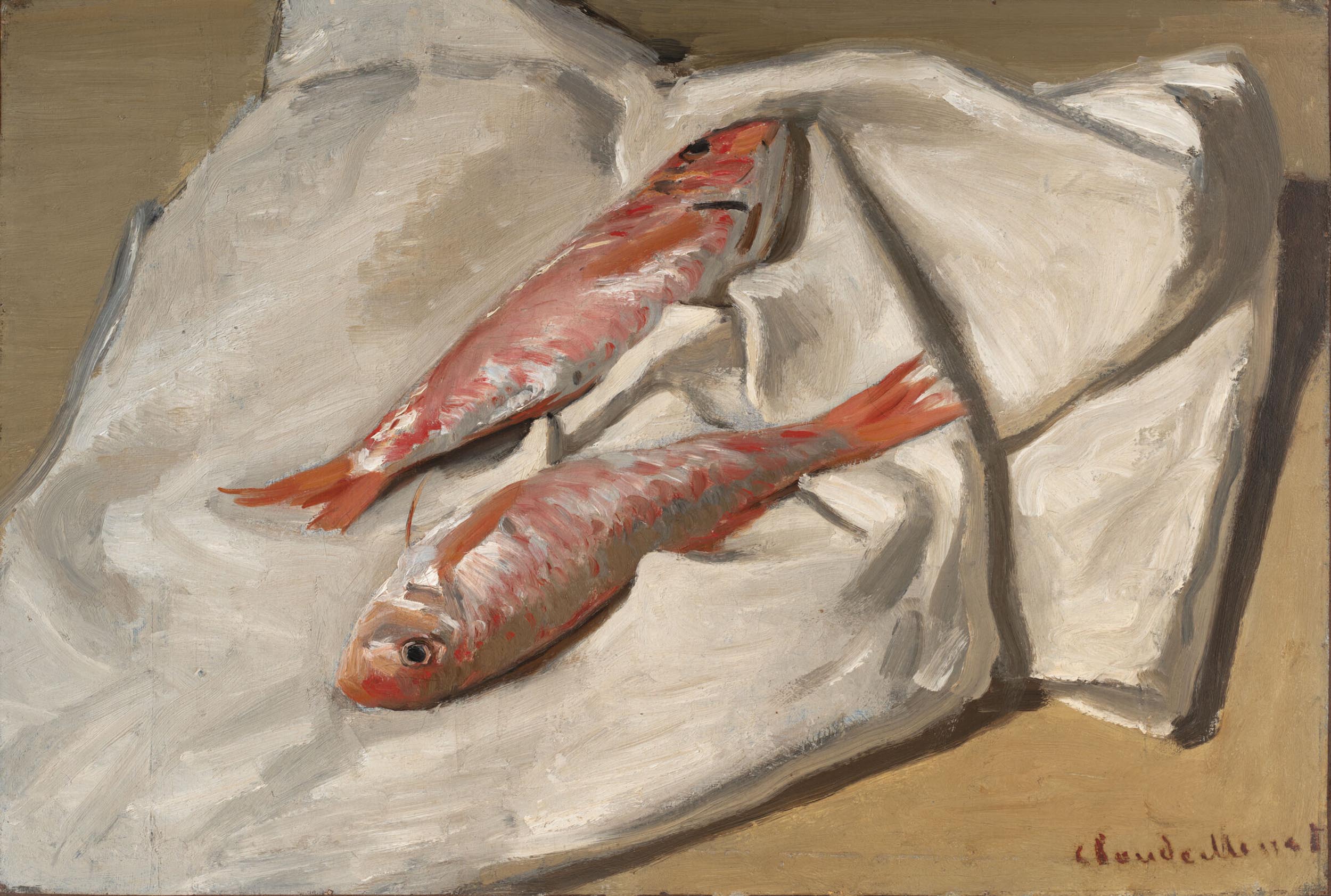

Vineyards at Auvers (1890)

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Vineyards at Auvers (1890), oil on canvas, Saint Louis Art Museum, Funds given by Mrs. Mark C. Steinberg

Description

I’m Charlotte Ogorek, the museum’s Rexroth project assistant. I am reading the description of Vineyards at Auvers (1890) in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Vincent van Gogh, a Dutch artist who lived from 1853 to 1890, painted the oil on canvas Vineyards at Auvers (1890) in June 1890. It is in the Saint Louis Art Museum collection courtesy of funds given by Mrs. Mark C. Steinberg.

Vineyards at Auvers (1890) is a horizontally oriented landscape painting measuring 39 and one-quarter by 44 and seven-eighths by five and one-quarter inches. In this landscape painting, van Gogh depicts a vast expanse of vineyards, surrounded by fencing, in the left and center foreground and again in the right background. Also in the background, stretching across the canvas, is the town of Auvers, complete with white buildings with red, gray, or green thatched roofs. Low masonry walls wind between these structures. A mountain range is visible beyond the buildings. A line of red poppies borders the left side of the painting.

Label

I’m Charlotte Ogorek, the museum’s Rexroth project assistant. I am reading the label for Vineyards at Auvers (1890) in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Vincent van Gogh, a Dutch artist who lived from 1853 to 1890, painted the oil on canvas Vineyards at Auvers (1890) in June 1890. It is in the Saint Louis Art Museum collection courtesy of funds given by Mrs. Mark C. Steinberg.

In this canvas, Vincent van Gogh seems to relish the contrast between the curving forms of grape vines and their askew arbors in the foreground, and the more structured geometries of the houses and fencing beyond. Red poppies provide a decorative border at left, their notes of color balanced by the orange roofs in the town. Van Gogh constructs the painting with his characteristic, heavily loaded brushstrokes.

In May 1890, after spending two years in the south of France, Van Gogh moved to the village of Auvers, just to the north of Paris. He spent two prolific months there, producing about seventy paintings, including Undergrowth with Two Figures, on view in the museum’s Gallery 227.

To the Market

I’m Kayla Jackson, the museum’s project manager. I am reading the "To the Market" section in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Paris’s medieval buildings were overcrowded due to the growing urban population. To modernize the city, Emperor Napoléon III ordered a substantial portion of “Old Paris” demolished and replaced with large boulevards, parks, and markets. Under the direction of the emperor and Baron Haussmann, the architect Victor Baltard designed the market complex Les Halles in a central Paris neighborhood that had long been associated with crime. Baltard’s architecture for the central markets was strikingly modern; he constructed towering pavilions of iron and glass that offered distinct buildings for different types of food. The vast scale of the market complex was meant to account for Paris’s massive growth, as the city had absorbed former outlying areas and migrant peasants. For over a century, Les Halles stood as an intersectional site between the urban and rural population.

Meat Haulers

Victor Gabriel Gilbert (French, 1847–1933), Meat Haulers, 1884, oil on canvas, Musée des beaux-arts de Bordeaux, Bx E 817

Description

I’m Kayla Jackson, the museum’s project manager. I am reading the description of the Meat Haulers in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Meat Haulers from 1884 is an oil on canvas painting by Victor Gabriel Gilbert, a French artist who lived from 1847 to 1933. It is in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux collection, and its registration number is Bx E 817.

Meat Haulers is an immense vertically oriented painting measuring 87 and thirteen-sixteenths by 74 by three and nine-sixteenths inches. In this picture, Gilbert depicts three men struggling with a large side of beef while additional carcasses hang behind it. In an interior space, two men in the left foreground use large poles to hoist a butchered cow off the device upon which it hangs. The man to the extreme right is dark-haired with a scraggly beard. A full-length white apron protects his clothes. On his left, another man wears a white cap, blue shirt, sleeves rolled past his elbows to show muscular forearms, and dark trousers. He braces himself as he also struggles with the side of beef. Both men wear wood clogs. On the left of the picture, the third man in this scene struggles with the animal's weight as it rests on his back. He is bent at the waist, arms clasped around the legs of the cow. He has a brown shirt with a white neck cloth and dark pants. He has an apron tied around his waist. In the background, the arched windows of the space in which they work are evident. The artist’s name, Victor Gilbert, and the date 1884, are written in the lower left corner.

Label

I’m Kayla Jackson, the museum’s project manager. I am reading the label for the Meat Haulers in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Meat Haulers from 1884 is an oil on canvas painting by Victor Gabriel Gilbert, a French artist who lived from 1847 to 1933. It is in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux collection, and its registration number is Bx E 817.

Working on the grand scale typical of the Paris Salon, the premier annual art exhibition in France, Victor Gabriel Gilbert depicts three workers moving a side of beef beneath Les Halles’ main pavilions. The neighborhood surrounding Les Halles had been the site of violent uprisings in Paris, and authors frequently used descriptions of animal carcasses as metaphors for revolutionaries’ corpses. The men here seem earnest in their labors, and Les Halles’ arches behind them seem to suggest a stabilizing social structure, in addition to its useful physical architecture. Gilbert frequently depicted the market during the 1870s and 1880s.

The Butcher’s Assistant

Aimé-Jules Dalou (French, 1838–1902), The Butcher’s Assistant, 1889–98, terra-cotta, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, PPS229

Description

I’m Kayla Jackson, the museum’s project manager. I am reading the description of The Butcher’s Assistant in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Aimé-Jules Dalou, a French artist who lived from 1838 to 1902, sculpted The Butcher’s Assistant from terra-cotta between 1889 and 1898. It is in the Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris collection. The registration number is PPS229.

The Butcher’s Assistant is a small vertically oriented sculpture measuring 19 and fifteen-sixteenths by seven and seven-eighths by six and eleven-sixteenths inches. Captured in terra-cotta is the form of a man, a butcher. He wears a long-sleeved, collared tunic over his clothing, cuffs rolled up over the wrists to show strong arms and hands. Over this, he wears an ankle-length apron hanging from his neck and tied at the waist. His hands rest at his waist, thumbs hanging through the apron tie. He appears to be wearing wooden clogs on his feet. He has short-cropped hair, a large nose, and deep-set eyes. Over his grimacing mouth is a bushy mustache.

Label

I’m Kayla Jackson, the museum’s project manager. I am reading the label for The Butcher’s Assistant in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Aimé-Jules Dalou, a French artist who lived from 1838 to 1902, sculpted The Butcher’s Assistant from terra-cotta between 1889 and 1898. It is in the Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris collection. The registration number is PPS229.

A student of renowned sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (whose work is also in this exhibition) Aimé-Jules Dalou entered the École des Beaux-Arts in 1853. After failing to win the prestigious travel fellowship, the Prix de Rome, four times, Dalou opted to earn income from private commissions rather than those sanctioned by the state. Moreover, due to his involvement with the the Paris Commune, the civil insurgency that followed the Siege of Paris in 1871, Dalou had to flee to London after its collapse and remained there until the French government granted him amnesty in 1880. Dalou was widely recognized for his portraiture and as a sculptor of genre subjects, like that of the Butcher with his Basket and The Butcher’s Assistant, and The Sower, displayed in another section of this exhibition.

The Square in Front of Les Halles

Victor Gabriel Gilbert (French, 1847–1933), The Square in Front of Les Halles, 1880, oil on panel, Musée d’art Moderne André Malraux, Le Havre, 163

Description

I’m Kayla Jackson, the museum’s project manager. I am reading the description of The Square in Front of Les Halles in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Victor Gabriel Gilbert, a French artist who lived from 1847 to 1933, painted The Square in Front of Les Halles in 1880 as an oil on panel. It is in the collection of the Musée d’art Moderne André Malraux in Le Havre. Its registration number is 163.

The Square in Front of Les Halles is a horizontally oriented street scene measuring 24 and eleven-sixteenths by 32 and eleven-sixteenths by one and seven-sixteenths inches. Here, Gilbert captures a bustling outdoor farmers market on a tree-lined street in Paris. In the background, a row of cream multi-storied buildings frames the central scene. In the center foreground of the composition, a middle-aged woman sits on a crate, her bent elbows resting on her knees. She wears a long blue skirt, dark coat, and kerchief wrapped over her head and tied at the chin. She looks straight ahead at the small black dog in front of her, unsmiling. Two large baskets containing leeks sit to her right. On her left is a small brown and white dog and a large black and white dog. They sit next to a large crate holding produce. Another woman, dressed in blue, walks in front of the canines carrying a large metal bucket. Behind her are additional produce stalls and sellers.

On the left side of the painting is another row of vegetable merchants. Interspersed amongst the rural individuals are well-dressed Parisians who browse and shop. Many of the ladies carry parasols, which are evident in the background. These umbrellas may also belong to the sellers to protect themselves and their wares from the sun. In the left foreground, an older girl dressed in a long blue dress and white apron holds two pieces of fruit in her outstretched hand, and a basket hangs from her elbow.

Label

I’m Kayla Jackson, the museum’s project manager. I am reading the label for The Square in Front of Les Halles in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Victor Gabriel Gilbert, a French artist who lived from 1847 to 1933, painted The Square in Front of Les Halles in 1880 as an oil on panel. It is in the collection of the Musée d’art Moderne André Malraux in Le Havre. Its registration number is 163.

In this scene, Victor Gabriel Gilbert depicts the individual vegetable sellers who set up stands on the Carreau, the walkways beside Les Halles’ main pavilions. The painting overflows with human interaction and vegetal splendor. A girl sells lemons; two dogs play; and women and men chat amid the lettuces, radishes, carrots, and leeks overflowing the tables. In the foreground, a seated female farmer in a patched dress anchors the composition with a timeless stoicism. Yet Gilbert also highlighted the activity of the modern city, suggesting the Carreau as a site of intersection between the urban and rural.

The Bourgeois Table

I’m Ryan Leary, a summer camp instructor at the museum. I am reading the "The Bourgeois Table" section in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Already in the nineteenth century, the French table depended on a global food production system. This system was chiefly controlled by colonial governments that leveraged resources and labor in favor of European economic gain.

Within France, the ostensibly apolitical nature of cuisine was used to promote national goals over partisan interests. Culinary practices could serve nationalistic objectives, as the fellowship of the table had the power to transcend political divisions. The artworks in this section highlight the domestic side of French culinary nationalism, showing that food intertwined the lives of the French populus across socio-economic and political lines.

Under the Lamp

Marie Bracquemond (French, 1840–1916), Under the Lamp, 1877, oil on canvas, Mr. and Mrs. R. Stephens Philips, Piedmont, CA

Description

I’m Ryan Leary, a museum’s summer camp instructor. I am reading the description of Under the Lamp in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Under the Lamp, created in 1877, is an oil on canvas by Marie Bracquemond, a French artist who lived from 1840 to 1916. It is in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. R. Stephens Philips in Piedmont, California.

Under the Lamp is a horizontally oriented painting measuring 27 and nine-sixteenths by 43 and five-sixteenths inches. A man and woman share a meal in this interior scene. Seated at a large table covered with a white cloth, a woman sits to the right of the composition and is viewed mainly from the back, her face in profile. She wears a high-necked dress with white ruffles and the neck and cuffs. The dress is striped in blue and a floral pattern. Her dark hair is pulled up into a high-updo style. Her left hand rests on the table before her; a gold bracelet adorns her wrist. Her right arm is bent, resting on the table. Her companion, a middle-aged man with dark hair and a goatee, sits across from her at the table, a green-shaded lamp hanging between them. He has a pleasant look as he gently smirks at the young woman. He wears a dark coat and rests his hands on the table. Between them, on the table, sits a large steaming bowl of soup in a blue and white vessel with a ladle alongside and a smaller spoon. Other items on the table include two bottles of wine, a carafe of water, a stack of plates, glasses, a bread roll, and a dish holding what appears to be carrots.

Label

I’m Ryan Leary, a museum’s summer camp instructor. I am reading the label for Under the Lamp in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Under the Lamp, created in 1877, is an oil on canvas by Marie Bracquemond, a French artist who lived from 1840 to 1916. It is in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. R. Stephens Philips in Piedmont, California.

Marie Bracquemond’s atmospheric painting captures an intimate dining scene—the painter Alfred Sisley, poised with a raised spoon, sits across from his future wife, Eugénie Lescouezec, who rests her hand on the table. A single gaslight illuminates the figures as steam rises from the bowl before them. Bracquemond meticulously represents the components of a simple meal: bread, soup, salt, pepper, oil, vinegar, and wine. The painting captures the humble pleasures of domestic dining but hints at an unspoken exchange between the couple.

The Preparations for a Hunting Meal

Jean-François Raffaëlli (French, 1850–1924), The Preparations for a Hunting Meal, 1875, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Gift of Wildenstein & Co., RF 2009 1

Description

I’m Ryan Leary, a summer camp instructor at the museum. I am reading the description of The Preparations for a Hunting Meal in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Jean-François Raffaëlli, a French artist who lived from 1850 to 1924, painted the oil on canvas, The Preparations for a Hunting Meal, in 1875. It is in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where it was a Gift of Wildenstein & Co. The registration number is RF 2009 1.

Preparations for a Hunting Meal is a grand horizontally oriented painting measuring 68 and one-eighth by 88 inches. This highly detailed painting demonstrates the results of a successful hunt. In the center of the work, a large deer hangs upside down from a hook at the top of the composition. Its upper body rests on the table, covered with a white cloth, and its head hangs off the side. To the right of the deer are rabbits and fowl, also ready to be cleaned for the meal. The abundance of feathers makes it challenging to determine the number of birds present. In the left foreground is a stool. To the left, on the table, is a bottle of wine, a water carafe, a meat pie, several small onions, and bunches of fresh herbs. In front of the table, in the lower left of the painting, is a smaller bench on which several fish rest.

Label

I’m Ryan Leary, a summer camp instructor at the museum. I am reading the label for The Preparations for a Hunting Meal in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Jean-François Raffaëlli, a French artist who lived from 1850 to 1924, painted the oil on canvas, The Preparations for a Hunting Meal, in 1875. It is in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where it was a Gift of Wildenstein & Co. The registration number is RF 2009 1.

The Preparations for a Hunting Meal overwhelms the viewer with bounty from land and sea. The cascade of recently hunted animals and fish and some long-stalked vegetables effectively divides the canvas diagonally. In the less-dense left side of the composition, Jean-François Raffaëlli includes a side of meat and two decanters. Juxtaposed with the animals yet to be cleaned and vegetables with their roots still attached these refined components suggest the passage from the hunt to the table.

Restaurant Culture

I’m Emily Agricola Holtrop, the museum’s director of Learning & Interpretation. I am reading the "Restaurant Culture" section in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

France, and Paris in particular, is associated with the birth of modern gastronomy and culinary arts in the Western world, which framed cooking as a profession, as opposed to a trade, and revolutionized restaurant culture. By the nineteenth century, culinary discourse was a cultural and intellectual endeavor for the French public. A refined palate became a point of national prestige, alongside philosophical ideals of the cuisine bourgeoise, which stressed simple preparations and quality ingredients.

The nation saw a growth of restaurants in and outside of Paris that gave rise to celebrity chefs such as Auguste Escoffier (1846–1935), who organized kitchen staff along military lines (brigade de cuisine—the system still used in many restaurants) and drew inspiration from dining practices abroad (service à la russe, in which dishes are served sequentially). These developments contributed to the emerging culinary ecosystem that aided France in forging an international identity, which, when expressed in such aphorisms as “France alone…is still capable of training chefs, whereas other countries train cooks,” could cross into chauvinism. Despite being a public space, restaurants became places for intimate exchanges, where friends socialized, and the bourgeoisie and upper classes put on ostentatious displays of their wealth.

The Artists’ Wives

James Tissot (French, 1836–1902), The Artists’ Wives, 1885, oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., and The Grandy Fund, Landmark Communications Fund, and “An Affair to Remember” 1982, 81.153

Description

I’m Emily Agricola Holtrop, the museum’s director of Learning & Interpretation. I am reading the description of The Artists’ Wives in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

The Artists’ Wives, from 1885, is an oil on canvas painted by James Tissot, a French artist who lived from 1836 to 1902. It is in the Chrysler Museum of Art collection and a Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., The Grandy Fund, Landmark Communications Fund, and “An Affair to Remember.” The registration number is 1982,81.153

The Artists’ Wives is a large vertically oriented painting measuring 69 one-quarter by 51 and three-quarters by five inches. This detailed composition features an alfresco (outdoor) dining scene. Here, tables with crisp white tablecloths welcome well-dressed Parisian patrons. In the foreground, the tables are ready for diners with clean glasses, cutlery, and bread ready for use and eating. Just behind this row of unoccupied tables is the figure our attention is focused on. She is a young woman in a high-necked red dress with small flowers. She wears a stylish red hat over her brown updo. While everyone is shown mostly from the back or side, she turns and looks directly at the viewer, smiling. Her dining companions include a woman to her left dressed in green and an older man with a long gray beard and a black top hat and suit sitting across from her. He is also facing the viewer. Several additional groupings like this populate this scene—well-dressed women and men out to dinner. Milling between the tables are several servers taking orders, opening wine, and delivering meals. In the background is a large and ornate structure, the front of which contains green awnings and a grand entrance. The multi-storied building behind is white stone with four over-life-size marble statues adorning a second-floor portico.

Label

I’m Emily Agricola Holtrop, the museum’s director of Learning & Interpretation. I am reading the label for The Artists’ Wives in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

The Artists’ Wives, from 1885, is an oil on canvas painted by James Tissot, a French artist who lived from 1836 to 1902. It is in the Chrysler Museum of Art collection and a Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., The Grandy Fund, Landmark Communications Fund, and “An Affair to Remember.” The registration number is 1982,81.153

With this painting, James Tissot captured the ritual gathering of artists and their wives to break bread the day before the opening of the annual Paris Salon. Set on the terrace of Ledoyen, a restaurant that remains a Parisian institution, Tissot’s bustling scene includes portraits of well-known artists such as the sculptor Auguste Rodin, whose bearded, bespectacled face appears near the center. The focus is on conviviality and merriment at a state-sponsored banquet on the eve of the year’s most important exhibition.

Card Players

Joseph-Claude Bail (French, 1862–1921), Card Players, 1897, oil on canvas, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la ville de Paris, PPP6

Description

I’m Emily Agricola Holtrop, the museum’s director of Learning & Interpretation. I am reading the description of the Card Players in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Joseph-Claude Bail, a French artist who lived from 1862 to 1921, painted the oil on canvas "Card Players" in 1897. It is in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and has the registration number PPP6.

Card Players is a sizeable horizontally oriented painting measuring 61 and seven-sixteenths by 80 and seven-eighths by five and seven-eighths inches. This interior scene captures four male kitchen apprentices at rest playing cards. Sitting at a wood table with a drawer partially open with a cloth spilling out, the figures each have their own personality. Starting on the left, a teen boy wears a long white apron, dark coat, and floppy chef’s hat. A cigarette in his mouth, he rests his chin on his left hand and holds his green playing cards in his right. Next to him and in the center of the painting, a younger boy, head just reaching the table, holds his cards in front of his smiling mouth. The third seated figure, on the right, wears a light red coat and has a cigarette in his outstretched right hand, his left hand, also stretched out, holds his cards. He looks directly at the viewer with a smile on his face. A fourth boy stands next to the table; he also has a light red shirt worn over a darker red shirt and a white shirt; all three layers rolled up at the wrist. He holds a glass in his right hand and rests his left on a large glass pitcher filled with water and lemons on a smaller table to his left.

Label

I’m Emily Agricola Holtrop, the museum’s director of Learning & Interpretation. I am reading the label for the Card Players in Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism.

Joseph-Claude Bail, a French artist who lived from 1862 to 1921, painted the oil on canvas Card Players in 1897. It is in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and has the registration number PPP6.

Joseph-Claude Bail was a specialist at depicting apprentices and entry-level kitchen workers, and here he offers a view of young cooks at leisure. Dressed in their aprons, playing cards and smoking, the four workers assume a variety of poses that recall paintings of soldiers amusing themselves between duties. The comparison is telling, as French kitchens adopted a military-inspired brigade system through the innovations of chefs such as Auguste Escoffier (1846 –1935). Bail renders this perspective on male communion between labors with a charming and incisive effect.