Celebrating Black History Month

by Cincinnati Art Museum

1/28/2022

February is Black History Month–a time to recognize the accomplishments and struggles of Black people throughout history. Join the Cincinnati Art Museum during this time of celebration by exploring works by Black artists in the museum’s permanent collection and upcoming special exhibitions David Driskell: Icons of Nature and History and Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop both on view February 25–May 15, 2022.

Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012)

Elizabeth Catlett (American, 1915–2012), Phillis Wheatley, 1973, bronze, Museum Purchase: Dr. Sandy Courter Memorial Fund, Lawrence Archer Wachs Fund, A. J. Howe Endowment, Henry Meis Endowment, Phyllis H. Thayer Purchase Fund, Israel and Caroline Wilson Fund, On to the Second Century Endowment, 1999.215, © Catlett Mora Family Trust/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. This artwork is currently on view in Gallery 211.

In 1973, at a conference on women poets, writer Margaret Walker suggested to Elizabeth Catlett that she make a sculpture of Phillis Wheatly, the first published African American poet. Wheatley was born in Senegal and sold into slavery as a child. The Wheatley family of Boston purchased her and provided her with a classical education. After the publication in 1773 of her Poems on Various Subjects Religious and Moral, Phillis Wheatley was emancipated. She was the author of about 145 poems and corresponded with George Washington and other leading statesmen.

Catlett used the only known portrait of Wheatley, the engraved frontispiece to her book, as a guide. She simplified the details of Wheatley’s clothing to produce an image of the poet that is both iconic and contemporary. She also abstracted Wheatley’s features to resemble an African mask, which contributes to the stoic appearance. These subtleties are significant both to Catlett’s interests as an artist and to Wheatley’s legacy.

During her graduate studies at the University of Iowa Catlett was influenced by painter Grant Wood, whom she admired for his belief in the artist’s social responsibility. From Mexican muralists, the African Art collection at the Barnes Foundation, and the European masters, including Van Gogh, Catlett drew on a range of creative traditions. Invigorated by the black power and feminist movements, she has specialized in images of empowered women, often Black or Mexican throughout her career.

Listen to a museum staff member discus Catlett’s work in this CAM Look Episode published on May 19, 2020.

Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872)

Robert S. Duncanson (American, 1821–1872), Blue Hole, Flood Waters, Little Miami River, 1851, oil on canvas, Gift of Norbert Heermann and Arthur Helbig, 1926.18. This artwork is currently on view in Gallery 107.

On May 30, 1861, the Cincinnati Gazette hailed Robert Duncanson, “the best landscape painter in the West.” The son of free African American parents, Duncanson painted in the Hudson River School tradition, achieving success despite the racial discrimination of the day.

The young Duncanson arrived in Cincinnati, where he would live for most of his life, about 1840. By that time the city was becoming established as the western outpost for landscape painting. Numerous artists called the city their home; significant exhibitions included works by the most influential figures, Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand; and growing wealth supported cultural life. Duncanson’s landscapes, such as Blue Hole, were inspired by Cole but were distinctively meditative. His landscapes and his equally sensitive still lifes earned him generous patronage, especially among Cincinnati’s prominent abolitionist sympathizers.

The beauty of the scenery around the Ohio River attracted Duncanson and other landscape painters such as William Sonntag and Worthington Whittredge. The Blue Hole, a deep, mirrorlike pool on the Little Miami River, a tributary of the Ohio, had been a favorite spot for artists since the early 1830s. (It is located now in John Bryan State Park.) Duncanson’s rendering of the site is distinguished by the simple geometry of its composition, its delicate palette of silvery blues and greens, its soft, fluent brushwork, and its sweetly poetic mood.

Listen to a museum docent discuss Duncanson’s work in this CAM Look episode published on June 26, 2020.

Terence Hammonds (b. 1976)

Terence Hammonds (American, b. 1976), Breakfront Pottery (Cincinnati, Ohio), Wave Pool (Cincinnati, Ohio; est. 2014), Protest Platter, 2020, glazed stoneware, 14”diameter, Cincinnati Art Museum, Museum Purchase with funds from the Friends of African American Art, © Terence Hammonds 2020. This artwork is currently not on view.

Terence Hammonds creates work, often print-based, that provokes dialogue about history, race, activism and change. This platter is part of an editioned set designed by Hammonds and created in collaboration with Breakfront Pottery (Cincinnati) and local refugee and immigrant artists of The Welcome Project of Wave Pool Gallery. In designing these Protest Platters, Hammonds collected and drew upon approximately 60 images of protest throughout history to create the printed transfers. “I wanted to grab things from various movements, from environmental, civil rights, immigrant rights, women’s rights and gay liberation movements,” he explained. “I chose images of people that were holding signs that were in first person and had the appearance of coming from a deeply personal space.” The form of the large, rimmed platter was designed in collaboration with Breakfront Pottery, while a group of emigre artists from the Welcome Project were employed to apply the transfers.

“I like to think of the platters as maybe having the reverse function of a ‘mammy jar’,” says Hammonds. “Whereas ‘mammy jars’ would reiterate racist stereotypes in subtle innocuous ways, I wanted the platters to remind us of the social struggles and the people who fought for change, and [who] empower us to keep up that fight in our daily lives.”

Listen to a museum docent discuss Hammond’s work in this CAM Look episode published on October 12, 2020.

Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000)

Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000), Fruits and Vegetables, 1959, tempera on hardboard, Mr. and Mrs. Harry S. Leyman Endowment, 2003.260, © 2016 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. This artwork is currently on view in Gallery 211.

Although narrative series such as The Migration of the Negro earned Jacob Lawrence early fame and success, scenes such as this one depicting daily life in a Black community were a recurring subject throughout his long career. Born in Atlantic City, Lawrence was raised and trained in Harlem, where he began to develop his signature style at an early age. Working in what he referred to as "Dynamic Cubism," Lawrence melded the fracturing of space he found in early twentieth-century Cubism with a vivid, patterned use of color that recalls traditional African textiles. In this painting, Lawrence used color and pattern to activate his composition: the striped awning at the upper right is echoed by the dress of the woman at lower left. Repeated colors and shapes of the fruit in the stands punctuate the image and flatten the space. Lawrence’s characteristic enlargement of heads and hands guides the viewer’s eye and emphasizes the movement and rhythm of the scene. In Fruits and Vegetables, Lawrence straddled the line between abstraction and representation: the action takes place in a believable space created by effective layering of elements, yet the painting is simultaneously a virtuoso display of flat color and pattern.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Lawrence’s work in this CAM Look episode published on May 12, 2020.

Horace Pippin (1888–1946)

Horace Pippin (American, 1888–1946), Christmas Morning, Breakfast, 1945, oil on canvas, The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, 1959.47. This artwork is currently on view in Gallery 211.

Horace Pippin shows the grandeur in the ordinary lives of common folk. In this autobiographical work, a mother serves pancakes while her son sits patiently with his hands folded in prayer, waiting to eat breakfast. The home’s poverty is evident in the exposed wallboards where large chunks of plaster have fallen away, and the mother’s life of unremitting labor is evident in her bowed back. Yet the painting glows with familial warmth between the two figures, and the neatness of the room suggests domestic order.

Pippin was self-taught, and regarded himself as a realist: "I don’t go around making up a whole lot of stuff. I paint it exactly the way it is and exactly the way I see it." His method was not academic. "Pictures just come to my mind," he explained, "and I tell my hearts to go ahead." Pippin developed a simplified, abstract manner based on a stylization of natural forms arranged in flat patterns. He used delicate line and subtle coloring for his poignant narratives.

Pippin took up painting after returning home from World War I. He had sustained permanent injury after being shot in the right shoulder and could no longer support himself as a laborer. During his lifetime, he achieved art world recognition for paintings such as this one.

Listen to a museum docent discuss Pippin’s work in this CAM Look episode published on December 23, 2020.

Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937)

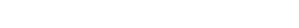

Henry Ossawa Tanner (American, 1859–1937), Flight into Egypt, circa 1907–12, oil on canvas in hand-carved and gilded frame, Fanny Bryce Lehmer Endowment, 2002.47. This artwork is currently on view in Gallery 216.

Ghostly figures move stealthily across the foreground in this simplified composition, with its low horizon line and unearthly blue sky. For Henry Ossawa Tanner, whose father was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, biblical themes like the Flight into Egypt provided a means to express his family traditions and spirituality. Tanner may have associated this story from the Book of Matthew, in which the Holy Family flees into the desert to escape persecution by King Herod, with his own struggles against racism and with the experiences of African Americans generally. Tanner settled in France, finding his work judged on its merits there without concern for his race. He owed his Paris education to the support of Bishop Joseph Crane Hartzell and his wife Clara, a Cincinnatian, who arranged for his first solo exhibition, held in Cincinnati in 1890. When the paintings failed to sell, the couple bought them to fund the artist’s studies abroad.

Kehinde Wiley (b. 1977)

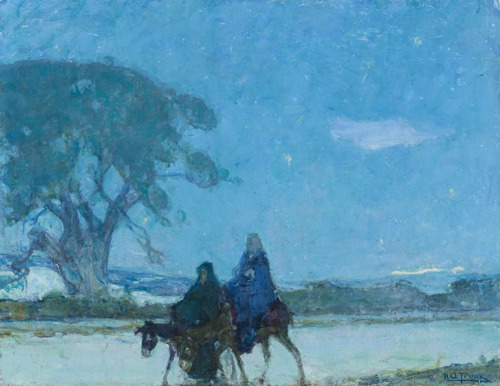

Kehinde Wiley (American, b. 1977), Portrait of Andries Stilte II, 2006, oil and enamel on canvas, Columbus Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, Derby Fund, courtesy of the Artist and Roberts and Tilton, Culver City, CA, L8.2021. This artwork is currently on loan in Gallery 150.

Kehinde Wiley challenges history through heroic portraits that reference Old Master paintings by Gainsborough, Titian, Reynolds, and leading artists regularly studied in art history. Identifying subjects from his everyday life in New York, and more recently Senegal, Wiley elevates Black figures through postures and adornments historically assigned to royalty and aristocratic descent in art. His personages take on poses found in classical European paintings and sculptures connoting influence and power.

Wiley’s larger-than-life figures interrupt the usual tropes of portrait painting, blurring the boundaries between traditional and contemporary modes of representation. Here, in conversation with Antwoine Washington across the gallery, we are asked to consider why these images convey surprise and dissonance from our own expectations. This painting, on loan from the Columbus Museum of Art, is an early fine example of Wiley’s work leading into his recent bronze sculpture, soon also to be seen at the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Explore more works by Black artists in the museum’s permanent collection with this self-guided tour through our galleries.